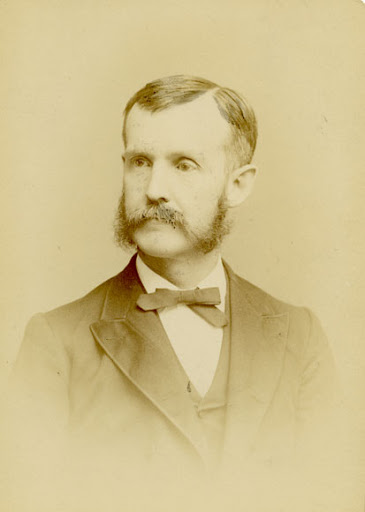

"Silent Times, A Book to Help in Reading the Bible into Life!" by J.R. Miller, 1886

You will find it helpful to READ the texts--as you LISTEN to the audios.

The TEXTS for the entire 24 chapter book, can be bound here:

https://gracegems.org/C/Miller_silent_times.htm

The AUDIOS for the entire 24 chapter book can be bound here:

https://www.gracegems.org/SermonAudio.htm?sa_ac...

J.R. Miller's "Silent Times, A Book to Help in Reading the Bible into Life" has been professionally read, and graciously supplied by Christopher Glyn. Please visit his YouTube channel at:

https://www.youtube.com/c/ChristopherGlyn where you can view a wide variety of Christopher's devotional readings with read-a-long texts online.

2 Timothy 3:16

Psalm 19:7-11

Puritans Spurgeon Edwards Pink Ryle Devotional meditation prayer Christ trials Calvin Luther reformed Calvinistic grace sovereign election predestination

Comments

Your comment has been submitted and is awaiting moderation. Once approved, it will appear on this page.

Be the first to comment!