The main theological topic addressed in John Newton's article "Union With Christ" is the profound and transformative nature of the believer's union with Christ. Newton argues that this union is characterized by its richness in privilege, deep intimacy, and unshakeable security, which cannot be satisfactorily depicted using earthly analogies. He illustrates this union through four comparisons, including believers being anchored to Christ as a solid rock, as branches connected to the vine, as members of a body incorporated in Christ, and as heirs of God through His grace. Newton supports his assertions with Scripture references including 1 John 17:21, which emphasizes the oneness of Christ and believers, and Ezekiel 16:1-63, which depicts believers’ transformation through their union with Christ. Ultimately, this union is presented as foundational to the believer's identity and life, urging them to walk in a manner worthy of the God who calls them into His kingdom.

Key Quotes

“The union of a believer with Christ is so intimate, so unalterable, so rich in privilege, so powerful in influence that it cannot be fully represented by any description or similitude taken from earthly things.”

“By nature we are separated from the divine life as branches broken off, withered, and fruitless. But grace through faith unites us to Christ, the living Vine.”

“Well may we say, What has God wrought? How inviolable is the security, how inestimable the privilege, how inexpressible the happiness of a believer!”

“How greatly is he indebted to grace! He was once afar off, but is brought near to God by the blood of Christ; he was once a child of wrath, but is now an heir of everlasting life.”

What does the Bible say about union with Christ?

The Bible teaches that believers are united with Christ, symbolizing an intimate and inseparable relationship, as seen in passages like John 17:21.

John 15:1-5, Ephesians 4:15-16, John 17:21

Why is union with Christ important for Christians?

Union with Christ is paramount for Christians as it ensures their salvation, identity, and empowerment for godly living.

Romans 4:5-8, John 15:5, Ephesians 2:19-22

How do we know the doctrine of union with Christ is true?

The truth of the doctrine of union with Christ is evidenced in Scripture and the transformative experiences of believers throughout history.

Galatians 2:20, Romans 6:5, Ephesians 2:4-6

Dear Sir,

The union of a believer with Christ is so intimate, so unalterable, so rich in privilege, so powerful in influence, that it cannot be fully represented by any description or similitude taken from earthly things. The mind, like the sight, is incapable of apprehending a great object, without viewing it on different sides. To help our weakness, the nature of this union is illustrated, in the Scripture, by four comparisons, each throwing additional light on the subject, yet all falling short of the thing signified.

In our natural state, we are driven and tossed about, by the changing winds of opinion, and the waves of trouble, which hourly disturb and threaten us upon the uncertain sea of human life. But faith, uniting us to Christ, fixes us upon a sure foundation, the Rock of Ages, where we stand immovable, though storms and floods unite their force against us.

By nature we are separated from the divine life, as branches broken off, withered and fruitless. But grace, through faith, unites us to Christ the living Vine, from whom, as the root of all fullness, a constant supply of sap and influence is derived into each of his mystical branches, enabling them to bring forth fruit unto God, and to persevere and abound therein.

By nature we are hateful and abominable in the sight of a holy God, and full of enmity and hatred towards each other. By faith, uniting us to Christ, we have fellowship with the Father and the Son, and joint communion among ourselves; even as the members of the same body have each of them union, communion, and sympathy, with the head, and with their fellow-members.

In our natural estate, we were cast out naked and destitute, without pity, and without help, Ezek. 16:1-63; but faith, uniting us to Christ, interests us in his righteousness, his riches, and his honors. Our Redeemer is our husband; our debts are paid, our settlements secured, and our names changed.

Thus the Lord Jesus, in declaring himself the foundation, root, head, and husband, of his people, takes in all the ideas we can frame of an intimate, vital, and inseparable union. Yet all these fall short of truth; and he has given us one further similitude, of which we can by no means form a just conception until we shall be brought to see him as he is in his kingdom. John 27:21: "That they all may be one, as you, Father, are in me, and I in you; that they also may be one in us."

Well may we say, What has God wrought! How inviolable is the security, how inestimable the privilege, how inexpressible the happiness, of a believer! How greatly is he indebted to grace! He was once afar off, but he is brought near to God by the blood of Christ: he was once a child of wrath, but is now an heir of everlasting life. How strong then are his obligations to walk worthy of God, who has called him to his kingdom and glory!

PREFACE

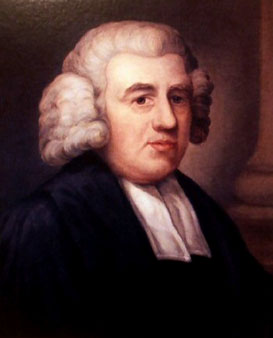

The memoirs of many are written at the particular request of their relations; but in publishing these of the late John Newton, I profess myself a volunteer; and my motives were the following: When I perceived my venerable friend bending under a weight of years, and considered how soon, from the very course of nature, the world must lose so valuable an instructor and example; when I reflected how common it is for hasty and inaccurate accounts of extraordinary characters to be obtruded on the public by debased writers, whenever more authentic documents are lacking above all; when I considered how striking a display such a life affords of the nature of true religion, of the power of Divine grace, of the mysterious but all-wise course of Divine Providence, and of the encouragement afforded for our dependence upon that Providence in the most trying circumstances— I say, on these accounts, I felt that the leading features of such a character of Mr. John Newton's should not be neglected, while it was easy to authenticate them correctly.

Besides which, I have observed a lack of books of a certain class for young people; and have often been inquired of by Christian parents for publications that might be interesting to their families, and yet tend to promote their best interests. The number, however, of this kind which I have seen, and which appeared helpful, is but small. For, as the characters and sentiments of some men become moral blights in society men, whose mouths seldom open but, like that of sepulchers, they reveal the putridity they contain, and infect more or less whoever ventures within their baneful influence; so the holy subject of these Memoirs was happily a remarkable instance of the reverse; the change that took place in his heart, after such a course of profligacy, affords a convincing demonstration of the truth and force of Christianity. Instead of proceeding as a blight in society, he became a blessing! His life was a striking example of the beneficial effects of the Gospel; and that not only from the pulpit, and by his pen—but also by his conversation in the large circle of his acquaintances, of which there is yet living a multitude of witnesses.

Impressed, therefore, with the advantages which I conceived would result from the publication of these Memoirs, I communicated my design some years ago to Mr. Newton. Whatever tended to promote that cause in which his heart had been long engaged, I was sure would not fail to obtain his concurrence. He accordingly promised to afford whatever letters and materials might be necessary, beyond those which his printed "Narrative" contained. He promised also to read over and revise whatever was added from my own observation; and he soon after brought me an account in writing, containing everything memorial which he recollected before the commencement of his "Narrative." I shall, therefore, detain the reader no longer than to assure him that the whole of the following Memoirs (except what relates to Mr. Newton's character) was submitted to him in MS. while he was capable of correcting it, and that it received his sanction.

Richard Cecil, April, 1808.

MEMOIRS

These Memoirs seem naturally to commence with the Account mentioned in the Preface, and which I here transcribe.

"I was born in London the 24th of July, 1725. My parents, though not wealthy, were respectable. My father was many years master of a ship in the Mediterranean trade. In the year 1748 he went Governor of York Fort in Hudson's Bay, where he died in the year 1750.

"My mother was a Dissenter, a pious woman, and a member of the late Dr. Jennings's Church. She was weak and sickly in health; and loved retirement; and, as I was her only child, she made it the chief business and pleasure of her life to instruct me, and bring me up in the nurture and admonition of the Lord. I have been told, that, from my birth, she had, in her mind, devoted me to the Christian ministry; and that, had she lived until I was of a proper age, I was to have been sent to Scotland to be educated. But the Lord had appointed otherwise. My mother died before I was seven years of age.

"I was rather of a sedentary turn, not active and playful, as boys commonly are—but seemed as willing to learn as my mother was to teach me. I had some mental capacity, and a retentive memory. When I was four years old, I could read (hard names excepted) as well as I can now; and could likewise repeat the answers to the questions in the Assembly's Shorter Catechism, with the Scripture proofs; and all Isaac Watts' smaller Catechisms, and his Children's Hymns.

"When my father returned from sea, after my mother's death, he married again. My new mother was the daughter of a substantial grazier. She seemed willing to adopt and bring me up; but, after two or three years, she had a son of her own, who engrossed the old gentleman's notice. My father was a very sensible, and a moral man, as the world rates morality; but neither he nor my step-mother was under the impressions of genuine religion. I was therefore much left to myself—to mingle with idle and wicked boys—and soon learned their ways!

"I never was at school but about two years; from my eighth to my tenth year. It was a boarding-school, at Stratford, in Essex. Though my father left me much to run about the streets—yet, when under his eye, he kept me at a great distance. I am persuaded he loved me—but he seemed not willing that I should know it. I was with him in a state of fear and bondage. His sternness, together with the severity of my schoolmaster, broke and overawed my spirit, and almost made me a dolt; so that part of the two years I was at school, instead of making a progress, I nearly forgot all that my good mother had taught me!

"The day I was eleven years old, I went on board my father's ship in Longreach. I made five voyages with him to the Mediterranean. In the course of the last voyage, he left me some months in Spain, with a merchant, a particular friend of his. With him I might have done well, if I had behaved well; but, by this time, my sinful propensities had gathered strength by habit! I was very wicked, and therefore very foolish; and, being my own worst enemy, I seemed determined that nobody should be my friend.

"My father left the sea in the year 1742. I made one voyage afterwards to Venice; and, soon after my return, was pressed into military service on board the Harwich. Then began my awfully mad career, as recorded in the 'Narrative;' to which, and to the 'Letters to a Wife,' I must refer you for any further dates and incidents."

John Newton, December 19, 1795

A few articles may be added to this account from the "Narrative," where we find that his pious mother stored his "memory with whole chapters, and smaller portions of Scripture, catechisms, hymns, and Christian poems; and often commended him with many prayers and tears to God." In his sixth year, he began to learn Latin, though the intended plan of his education was soon broken. He lost his pious mother, July 11th, 1782.

We also find, that, after his father's second marriage, John was sent to the school above-mentioned; and, in the last of the two years he spent there, a new teacher came, who observed and suited his temper. He learned Latin, therefore, with great eagerness; and, before he was ten years old. But, by being pushed forward too fast, and not properly grounded (a method too common in inferior schools) he soon lost all he had learned.

In the next and most remarkable period of Mr. Newton's life, we must be conducted by the above-mentioned "Narrative". It has been observed, that, at eleven years of age, he was taken by his father to sea. His father was a man of remarkably good sense, and great knowledge of the world. He took much care of his son's morals—but could not supply a mother's part. The father had been educated at a Jesuit's College, near Seville in Spain; and had an air of such distance and severity in his carriage—as discouraged his son, who always was in fear when before him, which deprived him of that influence he might otherwise have had.

From this time to the year 1742, Mr. Newton made several voyages—but at considerable intervals. These intervals were chiefly spent in the country, excepting a few months in his fifteenth year, when he was placed, with a very advantageous prospect, at Spain, already mentioned.

About this period of his life, with a temper and conduct exceedingly vacillating, he was often disturbed with religious convictions; and, being from a child fond of reading, he met with Bennett's "Christian Oratory," and, though he understood little of it, the course of life it recommended appeared very desirable to him. He therefore began to pray, to read the Scriptures, to keep a diary, and thought himself 'religious'; but soon became weary of it, and gave it up.

He then learned to curse and to blaspheme; and was exceedingly wicked when out of the view of his parents, though at so early a period.

Upon his being thrown from a horse near a dangerous hedge-row, his conscience suggested to him the dreadful consequences of appearing in such a wicked state before God. This put him, though but for a time, upon breaking off his profane practices; but the consequence of these struggles between sin and conscience was, that on every relapse—he sunk into still greater depths of wickedness! He was roused again, by the loss of a companion who had agreed to go with him one Sunday on board a 'man of war' ship. Mr. Newton providentially coming too late, the boat had gone without him, and had sunk, by which his companion and several others were drowned. He was exceedingly affected, at the funeral of this companion, to think that by the delay of a few minutes (which at the time occasioned him much anger) his life had been preserved; but this also was soon forgotten. The perusal of the "Family Instructor" produced another temporary reformation. In short, he took up and laid aside a religious profession three or four different times, before he was sixteen years of age.

"All this while," says he, "my heart was insincere. I often saw the necessity of religion, as a means of escaping hell; but I loved sin, and was unwilling to forsake it. I was so strangely blind and stupid, that, sometimes when I have been determined upon things which I knew were sinful, I could not go on quietly until I had first dispatched my ordinary task of prayer—in which I have grudged every moment of the time! When this was finished, my conscience was in some measure pacified, and I could rush into folly with little remorse!"

But his last reform was the most remarkable. "Of this period," says he, "at least of some part of it, I may say, in the Apostle's words, 'After the strictest sect of our religion, I lived a Pharisee!' I did everything that might be expected from a person entirely ignorant of God's righteousness, and desirous to establish his own. I spent the greatest part of every day in reading the Scriptures, and in meditation and prayer. I fasted often; I even abstained from all animal food for three months; I would hardly answer a question for fear of speaking an idle word; I seemed to bemoan my former miscarriages very earnestly, and sometimes with tears. In short, I became an Ascetic, and endeavored, as far as my situation would permit, to renounce going into the world, that I might avoid temptation."

This reformation, it seems, continued for more than two years. But he adds, "it was a poor religion! It left me in many respects under the power of sin; and, so far as it prevailed, only tended to make me gloomy, stupid, unsociable, and useless."

That it was a poor religion, and quite unlike that which he afterwards possessed, will appear from what immediately follows—for, had it been taken up upon more Scriptural ground, and attended with that internal evidence and satisfaction which true religion only brings—he could not so soon have fallen a dupe to such an infidel writer as Lord Shaftesbury. It was at a little shop in Holland, that he first met a volume of Shaftesbury's "Characteristics." The infidel book, called by Shaftesbury a "Rhapsody," suited the romantic turn of his mind. Unaware of its tendency, he imagined he had found a valuable guide. This book was always in his hand, until he could nearly repeat the whole "Rhapsody." Though it produced no immediate effect, it operated like a slow poison, and prepared the way for all that followed.

About the year 1742, his father, having lately come from a voyage, and not intending to return to sea, was contriving for John's settlement in the world. But, to settle a youth who had no spirit for business, who knew but little of men or things, who was of a romantic turn, and as he expressed it—a medley of religion, philosophy, and indolence, and quite averse to order—must prove a great difficulty.

At length a merchant in Liverpool, an intimate friend of his father, and afterwards a singular friend to the son, offered to send him for some years to Jamaica, and undertook the charge of his future welfare, This was consented to, and preparation made for the voyage, which was to leave the following week. In the meantime, he was sent by his father on some business to a place, a few miles beyond Maidstone, in Kent. But the journey, which was designed to last but three or four days, gave such a turn to his mind as roused him from his habitual indolence, and produced a series of important and interesting occurrences.

A few days before this intended journey, he received an invitation to visit some distant relations in Kent. They were particular friends of John's mother, who died at their house in Kent. But a coolness having taken place upon his father's second marriage, all fellowship between them had ceased. As his road lay within half a mile of their house, and he obtained his father's permission to call on them, he went there, and met with the kindest reception from these relatives. They had two daughters. It seems the elder sister, "Polly" had been intended, by both the mothers, for his future wife. Almost at first sight of this girl, then under fourteen years of age, he was impressed with such an affection for her, as appears to have equaled all that the writers of romance have ever imagined.

"I soon lost," says he, "all sense of religion, and became deaf to the remonstrance's of conscience and prudence; but my loving regard for her was always the same; and I may, perhaps, venture to say, that none of the scenes of misery and wickedness I afterwards experienced ever banished her a single hour together, from my waking thoughts for the seven following years."

His heart being now riveted to a particular object, everything with which he was concerned appeared in a new light. He could not now bear the thought of living at such a distance as Jamaica for four or five years—and therefore determined not to go there! He dared not communicate with his father on this point; but, instead of three days, he staid three weeks in Kent, until the ship had sailed without him—and then he returned to London. His father, though highly displeased, became reconciled; and, in a little time, he sailed with a friend of his father, to Venice.

In this voyage, being a common sailor, and exposed to the company of His comrades—he began to relax from the sobriety which he had preserved, in some degree, for more than two years. Sometimes, pierced with convictions, he made a few faint efforts, as formerly, to stop. And, though not yet absolutely profligate, he has making large strides towards a total apostasy from God. At length he received a remarkable check by a dream, which made a very strong, though not abiding, impression upon his mind.

I shall relate this dream in his own words, referring to his "Narrative" those who wish to know his opinion of dreams, and his application of this one in particular to his own circumstances.

"In my dream—the scene presented to my imagination was the harbor of Venice, where we had lately been. I thought it was night, and my turn for 'watch' upon the deck; and that, as I was walking to and fro by myself, a person came to me (I do not remember from whence) and brought me a ring, with an express charge to keep it carefully; assuring me, that, while I preserved that ring, I would be happy and successful; but, if I lost or parted with it, I must expect nothing but trouble and misery. I accepted the present and the terms willingly, not in the least doubting my own care to preserve it, and highly satisfied to have my happiness in my own keeping.

"I was engaged in these thoughts, when a second person came to me, and, observing the ring on my finger, took occasion to ask me some questions concerning it. I readily told him its virtues; and his answer expressed a surprise at my weakness, in expecting such effects from a mere ring! He reasoned with me some time, upon the impossibility of the thing; and at length urged me, in direct terms, to throw it away. At first I was shocked at the proposal; but his insinuations prevailed. I began to reason and doubt, and at last plucked the ring off my finger, and dropped it over the ship's side into the water, which it had no sooner touched, than I saw, at the same instant, a terrible fire burst out from a range of mountains (a part of the Alps) which appeared at some distance behind the city of Venice. I saw the hills as distinct as if awake, and that they were all in flames!

"I perceived, too late, my folly; and my tempter, with an air of insult, informed me, that all the mercy which God had in reserve for me—was comprised in that ring, which I had willfully thrown away! I understood that I must now go with him to the burning mountains, and that all the flames which I saw, were kindled on my account. I trembled, and was in a great agony; so that it was surprising that I did not then awake; but my dream continued.

"And, when I thought myself upon me point of a constrained departure for the fiery mountains, and stood self-condemned, without plea or hope, suddenly, either a third person, or perhaps the same who brought the ring at first (I am not certain which), came to me, and demanded the cause of my grief. I told him the plain case, confessing that I had ruined myself willfully—and deserved no pity. He blamed my rashness, and asked if I would be wiser, supposing I had my ring again. I could hardly answer to this, for I thought it was gone beyond recall. I believe, indeed, I had not time to answer, before I saw this unexpected friend dive down under the water, just in the spot where I had dropped it; and he soon returned, bringing the ring with him! The moment that he came on board, the flames in the mountains were extinguished, and my seducer left me!

"Then was the prey taken from the hand of the mighty, and the lawful captive delivered. My fears were at an end, and with joy and gratitude I approached my kind deliverer to receive the ring again. But he refused to return it, and spoke to this effect: 'If you should be entrusted with this ring again, you would very soon bring yourself into the same distress; you are not able to keep it; but I will preserve it for you, and, whenever it is needful, will produce it in your behalf. Upon this I awoke, in a state of mind not to be described; I could hardly eat, or sleep, or transact my necessary business, for two or three days. But the impression of my dream soon wore off, and in a little time I totally forgot it; and I think it hardly occurred to my mind again until several years afterwards."

Nothing remarkable took place in the following part of that voyage. Mr. Newton returned home in December 1743; and, repeating his visit to Kent, protracted his stay in the same imprudent manner he had done before. This so disappointed his father's designs for his interest, as almost to induce him to disown his son! Before any suitable employment offered again, this thoughtless son was conscripted by a lieutenant of the Harwich 'man of war', who immediately impressed and carried him on board. This was at a critical juncture, as the French fleets were hovering upon our coast. Here a new scene of life was presented; and, for about a month, much hardship endured. As a war was daily expected, his father was willing that John should remain in the navy, and procured him a recommendation to the captain, who sent him upon the quarter-deck as a midshipman. He might now have had ease and respect—had it not been for his unsettled mind and wild behavior. The companions he met with here, completed the ruin of his moral principles; though he affected to talk of virtue, and preserved some decency—yet his delight and habitual practice was wickedness.

His principal companion was a person of talents and regard—an expert and plausible infidel, whose zeal was equal to his address. "I have been told," says Mr. Newton, "that afterwards he was overtaken in a voyage from Lisbon in a violent storm; the vessel and people escaped—but a great wave broke on board, and swept him into eternity!" Being fond of this man's company, Mr. Newton aimed to display what smattering of reading he had; his companion, perceiving that Mr. Newton had not lost all the restraints of conscience, at first spoke in favor of religion; and, having gained Mr. Newton's confidence, and perceiving his attachment to the "Characteristics," he soon convinced his pupil that he had never understood that book. By objections and arguments, Mr. Newton's depraved heart was soon gained. He plunged into infidelity with all his spirit; and the hopes and comforts of the Gospel were renounced at the very time when every other comfort was about to fail.

In December, 1744, the Harwich was in the Downs, bound to the East Indies. The captain gave Mr. Newton permission to go on shore for a day—but, with his usual thoughtlessness, and following the dictates of a restless passion, he went to take a last visit of the object with which he was so infatuated. On new year's day he returned to the ship. The captain was so highly displeased at this rash step, that it ever after occasioned the loss of his favor.

At length they sailed from Spithead, with a very large fleet. They put in to Torbay, with a change of wind—but sailed the next day on its becoming fair weather. Several of the fleet were lost at leaving the place—but the following night the whole fleet was greatly endangered upon the coast of Cornwall, by a storm from the southward. The ship on which Mr. Newton was aboard escaped unhurt, though several times in danger of being run down by other vessels—but many suffered much; this occasioned their going back to Plymouth.

While they lay at Plymouth, Mr. Newton heard that his father, who had a financial interest in some of the ships lately lost, had come down to Torbay. He thought that, if he could see his father, he might easily be introduced into a service, which would be better than pursuing a long and uncertain voyage to the East Indies. It was his habit in those unhappy days, never to deliberate. As soon as the thought occurred, he resolved to leave the ship at all events; he did so, and in the worst manner possible.

He was sent one day in the boat to prevent others from desertion—but betrayed his trust, and deserted himself. Not knowing which road to take, and fearing to inquire lest he should be suspected—yet having some general idea of the country, he found, after he had traveled some miles, that he was on the road to Dartmouth. That day and part of the next day, everything seemed to go on smoothly. He thought that he would reach his father in about a two hour walk—when he was met by a small party of soldiers, whom he could not avoid or deceive; they brought him back to Plymouth, through the streets of which he proceeded guarded like a felon. Full of indignation, shame, and fear—he was confined two days in the guard-house; then sent on ship-board, and kept a while in irons; next he was publicly stripped and whipped, degraded from his office, and all his former companions forbidden to show him the least favor—or even to speak to him. As midshipman he had been entitled to command the ship, but being sufficiently haughty and vain, he was now brought down to a level with the lowest, and exposed to the insults of all. The state of his mind at this time, can only be properly expressed in his own words:

"As my present situation was uncomfortable, my future prospects were still worse; the evils I suffered were likely to grow heavier every day. While my catastrophe was recent, the officers and my fellow sailors were somewhat disposed to screen me from ill usage—but, during the little time I remained with them afterwards, I found them cool very fast in their endeavors to protect me. Indeed, they could not avoid such conduct without running a great risk of sharing punishment with me; for the captain, though in general a humane man, who behaved very well to the ship's company, was almost implacable in his resentment towards me, and took several occasions to show it! And the voyage was expected to be (as it proved) for five years! Yet nothing I either felt or feared distressed me so much as to see myself thus forcibly torn away from the object of my affections, under a great improbability of ever seeing her again, and a much greater improbability of returning in such a manner as would give me hope of seeing her become my wife.

"Thus I was as miserable on all sides—as could well be imagined. My heart was filled with the most excruciating passions: eager desire, bitter rage, and black despair!

"Every hour exposed me to some new insult and hardship, with no hope of relief or mitigation; no friend to take my part, nor to listen to my distress. Whether I looked inward or outward, I could perceive nothing but darkness and misery. I think no case, except that of a conscience wounded by the wrath of God, could be more dreadful than mine. I cannot express with what wishfulness and regret I cast my last looks upon the English shore; I kept my eyes fixed upon it, until, the ship's distance increasing, it insensibly disappeared. And, when I could see it no longer, I was tempted to throw myself into the sea, which (according to the wicked infidel system I had adopted) would put a end to all my sorrows at once. But the secret hand of God restrained me!"

During His passage to Madeira, Mr. Newton describes himself as a prey to the most gloomy thoughts. Though he had deserved all, and more than all the harsh treatment which he had met with from the captain—yet his pride suggested that he had been done a gross injustice. "And this so," says he, "wrought upon my bewitched heart, that I actually formed designs against the captain's life, and this was one reason which made me willing to prolong my own life. I was sometimes divided between the two. The Lord had now, to all appearance, given me up to judicial hardness of heart. I was capable of any wickedness. I had not the least fear of God before my eyes, nor (so far as I remember) the least sensibility of conscience. I was possessed with so strong a spirit of delusion, that I believed my own lie, and was firmly persuaded that after death—I should cease to be. Yet the Lord preserved me! Some intervals of sober reflection would at times take place; when I have chosen death rather than life—a ray of hope would come in (though there was little probability for such a hope) that I should yet see better days, that I might return to England, and have my wishes crowned, if I did not willfully throw myself away. In a word, my love to my dear "Polly" was now the only restraint I had left; though I neither feared God nor regarded man, I could not bear that she should think meanly of me when I was dead."

Mr. Newton had now been at Madeira some time. The business of the fleet being completed, they were to sail the following day; on that memorable morning he happened to sleep late in bed, and would have continued to sleep—but that an old companion, a midshipman, came down, between jest and earnest—and bid him rise. As he did not immediately comply, the midshipman cut down the hammock in which he lay; this obliged him to dress himself; and, though very angry, he dared not resent it—but was little aware that this person, without design, was a special instrument of God's providence.

Mr. Newton said little—but went upon deck, where he saw a man putting his own clothes into a boat, and informed Mr. Newton he was going to leave the ship. Upon inquiry, he found that two men from a Guinea ship, which lay near them, had entered on board the Harwich, and that the commodore (the late, Sir George Pecock) had ordered the captain to exchange two others in their place. Inflamed with this information, Mr. Newton requested that the boat be detained a few minutes; he then entreated the lieutenants to intercede with the captain that he might be dismissed upon this occasion. Though he had formerly behaved badly to these officer, they were moved with pity, and were disposed to serve him. The captain, who had refused to exchange him at Plymouth, though requested by Admiral Medley, was easily prevailed with now. In little more than half an hour from his being asleep in bed—he found himself discharged, and safely on board another ship; the events depending upon this change, will show it to have been the most critical and important.

The ship he now entered was bound to Sierra Leone, and the adjacent parts of what is called the Windward Coast of Africa. The commander knew his father, received him kindly, and made professions of assistance; and probably would have been his friend, if, instead of profiting by his former errors, he had not pursued a course, which if possible, was worse. He was under some restraint on board the Harwich—but, being now among strangers, he could sin without disguise.

"I well remember," says he, "that, while I was passing from one ship to the other, I rejoiced in the exchange, with this reflection, that I might now be as abandoned as I pleased, without any control. And, from this time, I was exceedingly vile indeed, little, if anything, short of that animated description of an almost irrecoverable state, which we have in 2 Peter 2:14 "With eyes full of adultery, they never stop sinning; they seduce the unstable; they are experts in greed—an accursed brood!" I not only sinned with a high hand myself—but made it my study to tempt and seduce others upon every occasion; nay, I eagerly sought occasion, sometimes to my own hazard and hurt."

By this conduct he soon forfeited the favor of his captain; for, besides being careless and disobedient, upon some imagined affront, he employed his mischievous wit in making a song to ridicule the captain—as to his ship, his designs, and his person; and he taught it to the whole ship's company!

He thus proceeded for about six months, at which time the ship was preparing to leave the coast—but, a few days before she sailed, the captain died. Mr. Newton was not upon much better terms with his mate, who succeeded to the command, and upon some occasion had treated him badly. He felt certain, that if he went in the ship to the West Indies, the mate would have put him on board a man of war, a consequence more dreadful to him than death itself! To avoid this, he determined to remain in Africa, and pleased himself with imagining it would be an opportunity of improving his fortune.

Upon that part of the coast there were a few white men settled, whose business it was to purchase slaves, etc. and sell them to the ships at an higher price. One of these, who had first landed in circumstances similar to Mr. Newton's, had acquired considerable wealth. This man had been in England, and was returning in the same vessel with Mr. Newton, of which he owned a quarter part. His example impressed Mr. Newton with hopes of the same success; and he obtained his discharge upon condition of entering into the trader's service, to whose generosity he trusted without the precaution of terms. He received, however, no compensation for his time on board the ship—but a bill upon the owners in England; which, in consequence of their failure, was never paid; the day, therefore, on which the vessel sailed, he landed upon the island of Benanoes, like one shipwrecked, with little more than the clothes upon his back.

"The two following years," says he, "of which I am now to give some account, will seem as an absolute blank in my life—but, I have seen frequent cause since to admire the mercy of God in banishing me to those distant parts, and almost excluding me from all society, at a time when I was filled with evil and mischief; and, like one infected with a pestilence, was capable of spreading my infectious evil, wherever I went! But the Lord wisely placed me where I could do little harm. The few I had to converse with were too much like myself; and I was soon brought into such abject circumstances, that I was too low to have any influence. I was rather shunned and despised, than imitated; there being few even of the Negroes themselves, during the first year of my residence—but thought themselves too good to speak to me. I was an outcast, ready to perish—but the Lord beheld me with mercy; he even now bid me to live; and I can only ascribe it to his secret upholding power, that what I suffered in this interval, did not bereave me either of my life or senses."

Mr. Newton's new master had resided near Cape Mount—but at this time had settled at the Plantanes, on the largest of the three islands. It is low and sandy, about two miles in circumference, and almost covered with palm-trees. They immediately began to build a house. Mr. Newton had some desire to retrieve his time and character, and might have lived tolerably well with his master, if this man had not been much under the direction of a black woman, who lived with him as a wife, and influenced him against his new servant. She was a person of some consequence in her own country, and he owed his first rise to her influence.

This woman, for reasons not known, was strangely prejudiced against Mr. Newton from the first. He also had unhappily a severe fit of illness, which attacked him before he had opportunity to show what he could or would do in the service of his master. Mr. Newton was sick when his master sailed to Rio Nuna, and was left in the hands of this cruel black woman. He was taken some care of at first—but, not soon recovering, her attention was wearied, and she entirely neglected him. Sometimes it was with difficulty he could procure a draught of cold water when burning with a fever! His bed was a mat, spread upon a board, with a log for his pillow. Upon His appetite returning, after the fever left him, he would gladly have eaten—but no one gave him any food. She lived in plenty—but scarcely allowed him sufficient to sustain life, except now and then, when in the highest good humor, she would send him scraps from her own plate after she had dined. And this (so greatly was he humbled) he received with thanks and eagerness, as the most needy beggar does an alms.

"Once," says he, "I well remember, I was called to receive this bounty from her own hand—but, being exceedingly weak and feeble, I dropped the plate. Those who live in plenty can hardly conceive how this loss touched me—but she had the cruelty to laugh at my disappointment; and, though the table was covered with dishes (for she lived much in the European manner), she refused to give me any more. My distress has been at times so great, as to compel me to go by night, and pull up roots in the plantation (though at the risk of being punished as a thief), which I have eaten raw upon the spot, for fear of discovery. The roots I speak of are very wholesome food, when boiled or roasted—but as unfit to be eaten raw. The consequence of this diet, which, after the first experiment, I always expected, and seldom missed, was to make me vomit; so that I have often returned as empty as I went; yet necessity urged me to repeat the trial several times. I have sometimes been relieved by strangers; yes, even by the black slaves—who have secretly brought me victuals (for they dared not be seen to do it) from their own slender pittance. Next to abject poverty, nothing sits harder upon the mind than scorn and contempt, and of this likewise I had an abundant measure."

When slowly recovering, the same woman would sometimes pay Mr. Newton a visit; not to pity or relieve—but to insult him. She would call him worthless and indolent, and compel him to walk; which when he could scarcely do, she would set her attendants to mimic his motions, to clap their hands, laugh, throw limes at him, and sometimes they would even throw stones. But though her attendants were forced to join in this treatment, Mr. Newton was rather pitied than scorned, by the lowest of her slaves, on her departure.

When his master returned from the voyage, Mr. Newton complained of ill usage—but was not believed. And, as he complained in her hearing, he fared worse for it. He accompanied his master in his second voyage, and they agreed pretty well, until his master was persuaded by a another trader that Mr. Newton was dishonest. This seems to be the only vice with which he could not be charged; as his honesty seemed to be the last remains of a good education which he could now boast of. And though his great distress might have been a strong temptation to fraud, it seems he never once thought of defrauding his master in the smallest matter. The charge, however, was believed, and he was condemned without evidence. From that time he was treated very harshly; whenever his master left the vessel, he was locked upon deck with a pint of rice for his day's allowance, nor had he any relief until his master's return.

"Indeed," says he, "I believe I would have been nearly starved—but for an opportunity of catching fish sometimes. When fowls were killed for my master's own use, I seldom was allowed any part but the entrails, to bait my hooks with; and, at the changing of the tides, when the current was still, I used generally to fish, (at other times it was not practicable,) and I very often succeeded. If I saw a fish upon my hook, my joy was little less than any other person would have found in the accomplishment of the scheme he had most at heart. Such a fish, hastily broiled, or rather half burnt, without salt, sauce, or bread, has afforded me a delicious meal. If I caught none, I might, if I could, sleep away my hunger until the next return of low tide, and then try again.

"Nor did I suffer less from the inclemency of the weather, and the lack of clothes. The rainy season was now advancing; my whole wardrobe was a shirt, a pair of trowsers, a cotton handkerchief instead of a cap, and a cotton cloth about two yards long; and, thus clothed, I have been exposed for twenty, thirty, perhaps near forty hours together, in incessant rains accompanied with strong gales of wind, without the least shelter, when my master was on shore. I feel to this day some faint returns of the violent pains I then contracted. The excessive cold and wet I endured in that voyage, and so soon after I had recovered from a long sickness, quite broke my constitution and my spirits; the latter were soon restored—but the effects of the former still remain with me, as a needful memento of the service and the wages of sin."

In about two months they returned, and the rest of the time which Mr. Newton spent with his master was chiefly at the Plantanes, and under the same regimen as has been mentioned. His heart was now bowed down—but not at all to a wholesome repentance. While his spirits sunk, the language of the prodigal was far from him; destitute of resolution, and almost of all reflection, he had lost the fierceness which fired him when on board the Harwich, and rendered him capable of the most desperate attempts—but he was no further changed than a tiger tamed by hunger.

However strange it may appear, he attests it as a truth, that, though destitute both of food and clothing, and depressed beyond common wretchedness, he could sometimes collect his mind to mathematical studies. Having bought Barrow's Euclid at Plymouth, and it being the only volume he brought on shore, he used to take it to remote corners of the island, and draw his diagrams with a long stick upon the sand. "Thus," says he, "I often beguiled my sorrows, and almost forgot my feelings; and thus without any other assistance I made myself in a good measure master of the first six books of Euclid."

"With my staff, I passed this Jordan, and now I am become two bands." These words of Jacob might well affect Mr. Newton, when remembering the days in which he was busied in planting some lime or lemon trees. The plants he put into the ground were no higher than a young gooseberry bush. His master and mistress, in passing the place, stopped a while to look at him; at length his master said, "Who knows but, by the time these trees grow up and bear fruit, you may go home to England, obtain the command of a ship, and return to reap the fruits of your labors? We see strange things sometimes happen."

"This," says Mr. Newton, "as he intended it, was a cutting sarcasm. I believe he thought it as probable that I should live to be king of Poland; yet it proved a prediction; and they (one of them at least) lived to see me return from England, in the capacity he had mentioned, and pluck some of the first limes from these very trees! How can I proceed in my story, until I raise a monument to the Divine goodness, by comparing the circumstances in which the Lord has since placed me, with what I was in at that time? Had you seen me, then go so pensive and solitary in the dead of night to wash my one shirt upon the rocks, and afterwards put it on wet, that it might dry upon my back while I slept; had you seen me so poor a figure, that when a ship's boat came to the island, shame often constrained me to hide myself in the woods, from the sight of strangers; especially, had you known that my conduct, principles, and heart—were still darker than my outward condition—how little would you have imagined, that one, who so fully answered to the description of the Apostle, "hateful and hating one another"—was reserved to be so peculiar an instance of the providential care and exuberant goodness of God! There was, at that time—but one earnest desire of my heart, which was not contrary and shocking both to religion and reason; that one desire, though my vile licentious life rendered me peculiarly unworthy of success, and though a thousand difficulties seemed to render it impossible, the Lord was pleased to gratify."

Things continued thus nearly twelve months. In this interval Mr. Newton wrote two or three times to his father, describing his condition, and desiring his assistance; at the same time signifying, that he had resolved not to return to England, unless his parent were pleased to send for him. His father applied to his friend at Liverpool, who gave orders accordingly, to a captain of his who was then fitting out for Sierra Leone.

Some time within the year, Mr. Newton obtained his master's consent to live with another trader, who dwelt upon the same island. This change was much to his advantage, as he was soon decently clothed, lived in plenty, was treated as a companion, and trusted with his effects to the amount of some thousand pounds. This man had several factories, and white servants in different places; particularly one in Kittam. Mr. Newton was soon appointed there, and had a share in the management of business, jointly with another servant. They lived as they pleased; business flourished; and their employer was satisfied.

"Here," says he, "I began to be wretch enough to think myself happy. There is a significant phrase frequently used in those parts, that such a white man is grown black. It does not intend an alteration of complexion—but disposition. I have known several, who, settling in Africa after the age of thirty or forty, have at that time of life, been gradually assimilated to the tempers, customs, and ceremonies of the natives, so far as to prefer that country to England; they have even become dupes to all the pretended charms, necromancies, amulets, and divination’s of the blinded Negroes, and put more trust in such things, than the wiser sort among the natives. A part of this spirit of infatuation was growing upon me (in time, perhaps, I might have yielded to the whole); I entered into closer engagements with the inhabitants, and would have lived and died a wretch among them, if the Lord had not watched over me for good. Not that I had lost those ideas which chiefly engaged my heart to England—but a despair of seeing them accomplished made me willing to remain where I was. I thought I could more easily bear the disappointment in this situation than nearer home. But, as soon as I had fixed my connections and plans with these views, the Lord providentially interposed to break them in pieces, and save me from ruin—in spite of myself!"

In the meantime, the ship that had orders to bring Mr. Newton home, arrived at Sierra Leone. The captain made inquiry for Mr. Newton there, and at the Benanas—but, finding he was at a great distance, thought no more about him. A special providence seems to have placed him at Kittam just at this time; for the ship coming no nearer than the Benanas, and staying but a few days, if he had been at the Plantanes he would not probably have heard of her until she had sailed; the same must have certainly been the event had he been sent to any other factory, of which his new master had several. But though the place he went to was a long way up a river, much more than a hundred miles distant from the Plantanes—yet he was still within a mile of the sea coast. The interposition was also more remarkable, as at that very juncture he was going in quest of trade, directly from the sea; and would have set out a day or two before—but that they waited for a few articles from the next ship that came, in order to complete the assortment of goods he was to take with him.

They used sometimes to walk to the beach, in hopes of seeing a vessel pass by—but this was very precarious, as at that time the place was not resorted to by ships of trade; many passed in the night, others kept a considerable distance from the shore; nor does he remember that any ship had ever stopped while he was there.

In Feb. 1747, his fellow-servant walking down to the beach in the forenoon, saw a vessel sailing by, and made a smoke-signal in token of trade. She was already beyond the place, and the wind being fair, the captain demurred about stopping; had Mr. Newton's companion been half an hour later, the vessel would have been beyond recall; when he saw her come to an anchor, he went on board in a canoe; and this proved the very ship already spoken of, which brought an order for Mr. Newton's return. One of the first questions the captain put was concerning Mr. Newton, and, understanding he was so near, the captain came on shore to deliver his message.

"Had," says he, "an invitation from home reached me when I was sick and starving at the Plantanes, I would have received it as the from the dead—but now, for the reasons already given, I heard it at first with indifference." The captain, however, unwilling to lose him, framed a story, and gave him a very plausible account of his having missed a large packet of letters and papers which he should have brought with him—but said he had it from his father's own mouth, as well as from his employer, that a person lately dead had left Mr. Newton 400 pounds per annum, and added, that, if embarrassed in his circumstances, he had express orders to redeem Mr. Newton though it should cost one half of his cargo. Every particular of this story was false.

But though his father's care and desire to see him was treated so lightly, and would have been insufficient alone to draw him from his retreat—yet the remembrance of Polly, the hopes of seeing her, and the possibility that his accepting this offer might once more put him in the way of gaining her hand, prevailed over all other considerations.

The captain further promised (and in this he kept his word) that Mr. Newton should lodge in his cabin, dine at his table, and be his companion, without being liable to service. Thus suddenly was he freed from a captivity of about fifteen months. He had neither a thought nor a desire of this change one hour before it took place—but, embarking with the captain, he in a few hours lost sight of his island residence.

The ship in which he embarked as a passenger was on a trading voyage for gold, ivory, wood, and bees' wax. Such a cargo requires more time to collect than one of slaves. The captain began his trade at Gambia, had been already four or five months in Africa; and during the course of a year after Mr. Newton had been with him, they ranged the whole coast as far as Cape Lopez, and more than a thousand miles further from England, than the place from whence he embarked.

"I have," says he, "little to offer worthy of notice in the course of this tedious voyage. I had no business to employ my thoughts—but sometimes amused myself with mathematics; excepting this, my whole life, when awake, was a course of most horrid impiety and profaneness. I know not that I have ever since met so daring a blasphemer. Not content with common oaths and imprecations, I daily invented new ones; so that I was often seriously reproved by the captain, who was himself a very passionate man, and not at all moral in his speech. From the stories I told him of my past adventures, and what he saw of my conduct, and especially towards the close of the voyage, when we met with many disasters, he would often tell me, that, to his great grief, he had a Jonah on board; that a curse attended me wherever I went; and that all the troubles he met with in the voyage were owing to his having taken me into his vessel!"

Although Mr. Newton lived long in the excess of almost every other extravagance, he was never, it seems, fond of alcohol; his father was often heard to say, that while his son avoided drunkenness, some hopes might be entertained of his recovery. Sometimes, however, in a frolic, he would promote a drinking-bout; not through love of liquor—but disposition to mischief; the last proposal he made of this kind, and at his own expense, was in the river Gabon, while the ship was trading on the coast.

Four or five of them sat down one evening to try who could hold out longest in drinking whisky and rum alternately. A large sea-shell supplied the place of a glass. Mr. Newton was very unfit for such a challenge, as his head was always incapable of bearing much liquor; he began, however, and proposed as a toast, some imprecation against the person who should start first; this proved to be himself. Fired in his brain, he arose and danced on the deck like a madman, and while he was thus diverting his companions, his hat went overboard. He endeavored eagerly to throw himself over the side into the boat, that he might recover his hat. He was half overboard, and would, in the space of a moment, have plunged into the water; when somebody caught hold of his clothes and pulled him back. This was an amazing escape, as he could not swim, even if he had been sober; the tide ran very strong; his companions were too much intoxicated to save him, and the rest of the ship's company were asleep.

Another time, at Cape Lopez, before the ship left the coast, he went, with some others, into the woods, and shot a wild cow; they brought a part of it on board, and carefully marked the place (as he thought) where the rest was left. In the evening they returned to fetch it—but set out too late. Mr. Newton undertook to be their guide—but, night coming on before they could reach the place, they lost their way. Sometimes they were in swamps, and up to the waist in water; and when they reached dry land, they could not tell whether they were proceeding towards the ship, or the contrary way. Every step increased their uncertainty, the night grew darker, and they were entangled in thick woods, which perhaps the foot of man had never trodden, and which abound with wild beasts; besides which, they had neither light, food, nor arms, while expecting a tiger to rush from behind every tree. The stars were clouded, and they had no compass whereby to form a judgment as to which way they were going. But it pleased God to secure them from the beasts; and after some hours of wandering, the moon arose, and pointed out the eastern quarter. It appeared then, that, instead of proceeding towards the sea, they had been penetrating into the country; at length, by the guidance of the moon, they made it back to the ship.

These, and many other deliverance's, produced at that time no beneficial effect. The admonitions of conscience, which from successive repulses had grown weaker and weaker, at length entirely ceased; and, for the space of many months, if not for some years, he had not a single check of that sort. At times he was visited with sickness, and believed himself to be near death—but had not the least concern about the consequences. "In a word," says he, "I seemed to have every mark of final impenitence and rejection; neither judgments nor mercies made the least impression on me."

At length, their business being finished, they left Cape Lopez and sailed homeward about the beginning of January, 1748. From there to England is perhaps more than seven thousand miles, if the circuits are included, which it is necessary to make on account of the trade-winds. They sailed first westward, until near the coast of Brazil; then northward, to the banks of Newfoundland, without meeting anything extraordinary. On these banks they stopped half a day to fish for cod; this was then chiefly for diversion, as they had provision enough, and little expected that those fish (as it afterwards proved) would be all they would have to exist on. They left March 1st, with a hard gale of wind westerly, which pushed them fast homewards. By the length of this voyage, in a hot climate, the vessel was greatly out of repair, and very unfit to endure stormy weather. The sails and cordage were likewise very much worn; and many such circumstances concurred to render what followed imminently dangerous.

Among the few books they had on board was one by Thomas A Kempis; Mr. Newton carelessly took it up, as he had often done before, to pass away the time—but which he had read with the same indifference as if it were a romance novel. But, in reading it this time, a thought occurred: "What if these things should be true!" He could not bear the force of the inference, and therefore shut the book, concluding that, true or false, he must abide the consequences of his own choice; and put an end to these reflections by joining in the vain life which came in his way.

"But now," says he, "the Lord's time was come, and the conviction I was so unwilling to receive, was deeply impressed upon me by a dreadful dispensation."

He went to bed that night in his usual carnal security—but was awakened from a sound sleep by the force of a violent wave which crashed on board; so much of it came down as filled the cabin in which he lay with water. This alarm was followed by a cry from the deck, that the ship was sinking! He essayed to go upon deck—but was met upon the ladder by the captain, who desired him to bring a knife. On his returning to his cabin to get the knife, another person went up in his place, who was instantly washed overboard. They had no time to lament him, nor did they expect to survive him long, for the ship was filling with water very fast. The sea had torn away the upper timbers on one side, and made it a mere wreck in a few minutes; so that it seems almost miraculous that any survived to relate the story. They had immediate recourse to the pumps—but the water increased against their efforts; some of them were set to bailing, though they had but eleven or twelve people to sustain this service. But, notwithstanding all they could do, the vessel was nearly full, and with a common cargo must have sunk—but, having a great quantity of bees'-wax and wood on board, which were lighter than water, and towards morning they were enabled to employ some means for safety. In about an hour's time, day began to break, and the wind abated; they expended most of their clothes and bedding to stop the leaks; over these they nailed pieces of boards; and, at last, the water within began to subside.

At the beginning of this scene, Mr. Newton was little affected; he pumped hard, and endeavored to animate himself and his companions. He told one of them, that in a few days this distress would serve for a subject over a glass of wine—but the man, being less hardened than himself, replied with tears, "No, it is too late now." About nine o'clock, being almost spent with cold and labor, Mr. Newton went to speak with the captain, and, as he was returning, said, almost without meaning, "If this will not do—the Lord have mercy upon us!" thus expressing, though with little reflection, his desire of mercy for the first time within the space of many years. Struck with his own words, it directly occurred to him, "What mercy can there be for me!"

He was, however, obliged to return to the pump, and there continued until noon, almost every passing wave breaking over his head, being, like the rest, secured by ropes, that they might not be washed away. He expected, indeed, that every time the vessel descended into the sea—she would rise no more; and though he dreaded death now, and his heart foreboded the worst, if the Scriptures, which he had long opposed, were true; yet he was still but half convinced, and remained for a time in a sullen frame—a mixture of despair and impatience. He thought, "if the Christian religion were true—then he could not be forgiven;" and was therefore expecting, and almost at times wishing, to know the worst of it.

The following part of his "Narrative" will, I think, be best expressed in his own words; "The 21st of March, is a day much to be remembered by me, and I have never allowed to pass wholly unnoticed since the year 1748. On that day the Lord sent from on high, and delivered me out of deep waters. I continued at the pump from three in the morning until nearly noon, and then I could do no more. I went and lay down upon my bed, uncertain, and almost indifferent whether I should rise again. In an hour's time I was called; and, not being able to pump, I went to the helm, and steered the ship until midnight, excepting a small interval for refreshment. I had here leisure and convenient opportunity for reflection. I began to think of my former religious professions, the extraordinary turns of my life, the calls, warnings, and deliverances I had met with, the licentious course of my life, particularly my unparalleled effrontery in making the Gospel history (which I could not be sure was false, though I was not yet assured it was true) the constant subject of profane ridicule. I thought, allowing the Scripture premises, there never was or could be such a vile sinner as myself; and then, comparing the advantages I had broken through, I concluded at first, that my sins were too great to be forgiven. The Scripture, likewise, seemed to say the same; for I had formerly been well acquainted with the Bible, and many passages, upon this occasion, returned upon my memory; particularly those dreadful passages, Pro. 1:24-31; Hebrews 6:4-6; and 2 Pe. 2:20, which seemed so exactly to suit my case and character.

"Thus, as I have said, I waited with fear and impatience to receive my inevitable doom. Yet, though I had thoughts of this kind, they were exceeding faint and disproportionate; it was not until after (perhaps) several years that I had gained some clear views of the infinite righteousness and grace of Christ Jesus my Lord, that I had a deep and strong apprehension of my state by nature and practice; and, perhaps, until then, I could not have borne the sight! So wonderfully does the Lord proportion the discoveries of sin and grace; for he knows our frame, and that, if he were to put forth the greatness of his power, a poor sinner would be instantly overwhelmed, and crushed as a moth!

"But, to return—When I saw, beyond all probability, that there was still hope of respite, and heard, about six in the evening, that the ship was freed from water, a gleam of hope arose. I thought I saw the hand of God displayed in our favor. I began to pray; I could not utter the prayer of faith; I could not draw near to a reconciled God, and call him Father; my prayer was like the cry of the ravens, which yet the Lord does not disdain to hear. I now began to think of that Jesus whom I had so often derided; I recollected the particulars of his life, and of his death; a death for sins not his own—but, as I remembered, for the sake of those who, in their distress, would put their trust in him. And how I chiefly wanted evidence. The comfortless principles of infidelity were deeply riveted; and I rather wished, than believed these things were real facts. Please observe, that I collect the strain of the reasoning and exercises of my mind in one view—but I do not say that all this passed at one time. The great question now was, how to obtain faith. I speak not of an appropriating faith (of which I then knew neither the nature nor necessity)—but how I should gain an assurance that the Scriptures were of Divine inspiration, and a sufficient warrant for the exercise of trust and hope in God.

"One of the first helps I received (in consequence of a determination to examine the New Testament more carefully) was from Luke 11:13. I had been sensible, that to profess faith in Jesus Christ, when, in reality, I did not believe his history—was no better than a mockery of the heart-searching God—but here I found the Holy Spirit spoken of, who was to be communicated to those who asked. Upon this I reasoned thus; If this book is true, the promise in this passage must be true likewise. I have need of that very Spirit, by which the whole was written, in order to understand it aright. He has engaged here to give that Spirit to those who ask; I must therefore pray for Him; and, if it is of God, he will make good his own word. My purposes were strengthened by John 7:17. I concluded from thence, that, though I could not say from my heart that I believed the Gospel—yet I would, for the present, take it for granted; and that, by studying it in this light, I would be more and more confirmed in it.

"If what I am writing could be perused by our modern infidels, they would say (for I too well know their manner) that I was very desirous to persuade myself into this opinion. I confess I was; and so would they be, if the Lord should show them, as he was pleased to show me at that time—the absolute necessity of some expedient to interpose between a righteous God and a sinful soul; upon the Gospel scheme, I saw at least a possibility of hope—but, on every other side, I was surrounded with black, unfathomable despair."

The wind being now moderate, and the ship drawing near to its port, the ship's company began to recover from their consternation, though greatly alarmed by their circumstances. They found that the water having floated their moveables in the hold, all the casks of provisions had been beaten to pieces by the violent motion of the ship. On the other hand, their livestock had been washed overboard in the storm. In short, all the provisions they saved, except the fish lately caught on the banks for amusement, and a little of the grain, which used to be given to the hogs, would have supported them but a week, and that at a scanty allowance. The sails, too, were mostly blown away; so that they advanced but slowly, even while the wind was fair. They imagined they were about a hundred leagues from land—but were in reality much further. Mr. Newton's leisure time was chiefly employed in reading, meditation on the Scriptures, and prayer for mercy and instruction.

Things continued thus for about four or five days, until they were awakened one morning by the joyful shouts of the watch upon deck, proclaiming the sight of land. The dawning was uncommonly beautiful; and the light, just sufficient to reveal distant objects, presented what seemed a mountainous coast, about twenty miles off, with two or three small islands; the whole appeared to be the north-west extremity of Ireland for which they were steering. They sincerely congratulated one another, having no doubt that if the wind continued, they would be in safety and plenty the next day. Their brandy, which was reduced to a little more than a pint, was, by the captain's orders, distributed among them; who added, "We shall soon have brandy enough!" They likewise ate up the remainder of their bread, and were in the condition of men suddenly reprieved from death.

But, while their hopes were thus excited, the mate sunk their spirits, by saying, in a graver tone, that he wished "it might prove land at last." If one of the common sailors had first said so, the rest would probably have beaten him. The expression, however, brought on warm debates, whether it was land or not—but the case was soon decided; for one of their fancied islands began to grow red from the approach of the sun. In a word, their land was nothing but clouds; and, in half an hour more, the whole appearance was dissipated.

Still, however, they cherished hope from the wind continuing fair—but of this hope they were soon deprived. That very day, their fair wind subsided into a calm; and, the next morning, the gale sprung up from the south-east, directly against them, and continued so for more than a two weeks afterwards. At this time the ship was so wrecked, that they were obliged to keep the wind always on the broken side, except when the weather was quite moderate; and were thus driven still further from their port in the north of Ireland, as far as Lewes, among the western isles of Scotland. Their station now was such, as deprived them of any hope of relief from other vessels. "It may indeed be questioned," says Mr. Newton "whether our ship was not the very first that had been in that part of the ocean at the same time of the year."

Provisions now began to fall short. The half of a salted cod was a day's subsistence for twelve people; they had no stronger liquor than water, no bread, hardly any clothes, and very cold weather. They had also incessant labor at the pumps, to keep the ship above water. Much labor and little food wasted them fast, and one man died under the hardship. Yet their sufferings were light when compared with their fears. Their bare allowance could continue but little longer; and a dreadful prospect appeared of their being either starved to death, or reduced to feed upon one another.

At this time Mr. Newton had a further trouble, peculiar to himself. The captain, whose temper was quite soured by distress, was hourly reproaching him as the sole cause of the calamity, and was confident that his being thrown overboard would be the only means of preserving them. The captain, indeed, did not intend to make the experiment—but "the continued repetition of this in my ears," says Mr. Newton, "gave me much uneasiness; especially as my conscience seconded his words; I thought it very probable, that all that had befallen us—was on my account; that I was at last found out by the powerful hand of God, and condemned in my own breast."

While, however, they were thus proceeding, at a time when they were ready to give up all for lost, and despair appeared in every countenance, they began to conceive hope from the wind's shifting to the desired point, so as best to suit that broken part of the ship, which must be kept out of the water, and so gently to blow, as their few remaining sails could bear. And thus it continued at an unsettled time of the year, until they were once more called up to see land, and which was really such. They saw the island of Tory, and the next day anchored in Lough Swilly, in Ireland, on the 8th of April, just four weeks after the damage they had sustained from the sea. When they came into this port, their very last victuals were boiling in the pot, and before they had been there two hours, the wind, which seemed to have been providentially restrained until they were in a place of safety, began to blow with great violence; so that, if they had continued at sea that night, they must, in all human estimation, have gone to the bottom! "About this time," says Mr. Newton, "I began to know that there is a God, who hears and answers prayer!"

Memoirs Part 2

Mr. Newton's history is now brought to the time of his arrival in Ireland, in the year 1748; and the progress he had hitherto made in religion will be best related in His own words. I shall, therefore, take a longer extract than usual, because it is important to trace the operation of real religion in the heart. Speaking of the ship in which he lately sailed, he says,

"There were no people on board to whom I could open myself with freedom concerning the state of my soul; none from whom I could ask advice. As to books, I had a New Testament, Stanhope, already mentioned, and a volume of Beveridge's Sermons; one of which, upon our Lord's Passion, affected me much. In perusing the New Testament, I was struck with several passages, particularly that of the fig-tree, Luke 13; the case of Paul, 1 Tim 1; but particularly that of the Prodigal, Luke 15. I thought that had never been so nearly exemplified as by myself. And then the goodness of the father in receiving, nay, in running to meet such a son, and this intended only to illustrate the Lord's goodness to returning sinners. Such reflections gaining upon me, I continued much in prayer; I saw that the Lord had interposed so far to save me, and I hoped he would do more. Outward circumstances helped in this place to make me still more serious and earnest in crying to him who alone could relieve me; and sometimes I thought I could be content to die even for lack of food—just so that I might but die a believer.

"Thus far I was answered, that before we arrived in Ireland, I had a satisfactory evidence in my own mind of the truth of the Gospel, as considered in itself, and of its exact suitableness to answer all my needs. I saw, that, by the way it was pointed out, God might declare not his mercy only—but his justice also, in the pardon of sin—on account of the obedience and sufferings of Jesus Christ. My judgment at that time, embraced the sublime doctrine of God manifest in the flesh, reconciling the world unto himself. I had no idea of those systems, which allow the Savior no higher honor than that of an upper servant, or at the most of a demi-god. I stood in need of an Almighty Savior; and such a one I found described in the New Testament.

"Thus far the Lord had wrought a marvelous thing; I was no longer an infidel; I heartily renounced my former profaneness, and had taken up some right notions; was seriously disposed, and sincerely touched with a sense of the undeserved mercy I had received, in being brought safely through so many dangers. I was sorry for my past misspent life, and purposed an immediate reformation. I was quite freed from the habit of swearing, which seemed to have been as deeply rooted in me as a second nature. Thus, to all appearance, I was a new man!

"But, though I cannot doubt that this change, so far as it prevailed, was wrought by the Spirit and power of God—yet still I was greatly deficient in many respects. I was in some degree affected with a sense of my enormous sins—but I was little aware of the innate evils of my heart. I had no apprehension of the spirituality and extent of the Law of God; or of the hidden life of a Christian, as it consists in communion with God by Jesus Christ; a continual dependence on him for hourly supplies of wisdom, strength, and comfort—was a mystery of which I had as yet no knowledge. I acknowledged the Lord's mercy in pardoning what was past—but depended chiefly upon my own resolution to do better for the time to come. I had no Christian friend or faithful minister to advise me that my strength was no more than my righteousness; and though I soon began to inquire for serious books—yet, not having spiritual discernment, I frequently made a wrong choice; and I was not brought in the way of evangelical preaching or conversation (except the few times when I heard—but understood not) for six years after this period. Those things the Lord was pleased to reveal to me gradually. I learned them, here a little and there a little, by my own painful experience, at a distance from the common means and ordinances, and in the midst of the same course of evil company and bad examples I had been conversant with for some time.

"From this period I could no more make a mock at sin, or jest with holy things; I no more questioned the truth of Scripture, and had a sense of the rebukes of conscience. Therefore I consider this as the beginning of my return to God, or rather of his return to me—but I cannot consider myself to have been a believer (in the full sense of the word) until a considerable time afterwards."