John Newton's "Letters to William Bull" presents a rich tapestry of pastoral wisdom, theological reflection, and personal correspondence highlighting the intricacies of Christian friendship and ministry. The main theological theme throughout the letters is the sovereignty of God in both personal suffering and communal trials, illustrated through Newton’s correspondence with Bull regarding church issues, personal afflictions, and the broader societal challenges of their time. The letters emphasize the importance of prayer and dependence on God's providence amidst life's uncertainties, drawing from Scripture for support; for instance, Newton references Psalm 71:9, pleading not to be forsaken in old age, and 1 Corinthians 15:10, attributing his transformation and calling to divine grace. The practical significance of these letters lies in its heartfelt expressions of Christian unity and exhortations toward steadfastness in faith, illustrating how the doctrine of providence can comfort and guide believers in tumultuous times.

Key Quotes

“Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity.”

“The Lord reigns. He governs the world and let men contrive and plot as they will; they are all instruments in his hand.”

“Blessed are the dead who die thus in the Lord; they rest from their labors and conflicts and are now before the throne.”

“Let us not be weary in doing or suffering the Lord's will for in due season we shall reap.”

What does the Bible say about friendship in the Christian life?

The Bible emphasizes the importance of deep, sincere friendships, reflecting God's love and grace among believers.

Hebrews 10:24-25, Psalm 133:1

Why is humility important for Christians?

Humility is crucial for Christians as it reflects the character of Christ and fosters a genuine walk with God.

Philippians 2:3-4, 1 Peter 5:5-6

How does God's providence work in the lives of Christians?

God's providence ensures that all events in a Christian's life are under His sovereign control for their ultimate good.

Romans 8:28, Proverbs 16:9

How can Christians effectively care for one another?

Christians can care for one another through acts of love, encouragement, and bearing each other's burdens.

Galatians 6:2, 1 Thessalonians 5:11

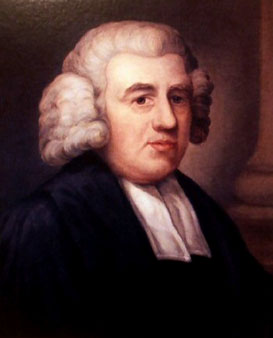

Mr. Bull became pastor of the Independent church at Newport Pagnell about the same time that Mr. Newton came to Olney. (The two places were but five miles apart.) The acquaintance between these friends did not commence until some time after this. No sooner, however, did they come really to know each other than this acquaintance speedily ripened into a very intimate, and, as it proved, a life-long friendship. In his Diary, at this time, Mr. Newton speaks again and again of the high esteem in which his friend was held. Thus he says: "I find few with whom I can converse with equal advantage, whose manner of thinking is so deep and solid." Again: "He has just called and spent an hour with me. I could sit silent half a day to listen to him, and am almost unwilling to speak a word for fear of preventing him." Once more: "I admire Mr. Bull; so humble, so spiritual, so judicious and so savory . . . I think he will be my most profitable companion in these parts."

The fellowship between Mr. Newton and Mr. Bull, as may be well supposed, was very frequent, so long as the former resided at Olney; and when he removed to London, there was abundant opportunity for its renewal, as Mr. Bull was in the habit, for many years, of preaching for several sabbaths at the Tabernacle and at Tottenham Court and Surrey Chapels. The flame of their affection burnt brightly to the last; for, as Mr. Newton writes in 1800, when to write had become a task, "If two needles are properly touched by a magnet, they will retain their sympathy for a long time. But if two hearts are truly united to the Heavenly Magnet, their mutual attraction will be permanent in time and to eternity. Blessed be the Lord for a good hope, that it is thus between you and me. I could not love you better if I saw or heard from you every day."

Mr. Bull was pastor of the church at Newport for fifty years; a church which he was enabled, by the blessing of God, to raise from a very low condition to a state of great prosperity. For a considerable portion of this time be also presided over a theological institution, in the formation of which Mr. Newton took a very active part, and the special design of which was to train suitable young men of evangelical sentiments for the Christian ministry, without regard to denominational distinctions.

"Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity!" Psalm 133:1

Dear Sir,

At present it is January with me — both within and without. The outward sun shines and looks pleasant — but his beams are faint, and too feeble to dissolve the frost.

So is it in my heart! I have many bright and pleasant beams of truth in my view — but cold predominates in my frost-bound spirit, and they have but little power to warm me!

I could tell a stranger something about Jesus, which would perhaps astonish him. Such a glorious person, such wonderful love, such humiliation, such a death! And then, what He is now in Himself, and what He is to His people. What a Sun! what a Shield! what a Life! what a Friend!

My tongue can run on upon these subjects sometimes, and could my heart keep pace with it — I would be the happiest fellow in the country!

Stupid creature! to know these things so well, and yet be no more affected with them!

Indeed, I have reason to be upon ill terms with myself. It is strange that pride should ever find anything in my experience to feed upon; but this completes my character for folly, vileness, and inconsistency — that I am not only poor — but proud! And though I am convinced I am a very wretch, as nothing before the Lord — I am prone to go forth among my fellow-creatures as though I were wise and holy!

You wonder what I am doing — and well you may. I am sure you would, if you lived with me. Too much of my time passes in busy idleness, too much in waking dreams. I aim at something — but hindrances from within and without make it difficult for me to accomplish anything. I have written three or four pages since you was here, in the little book I showed you. It is to be but about the size of a shilling pamphlet; and if I go on as I have begun, it may be finished before Christmas! I dare not say I am absolutely idle, or that I willfully waste much of my time. I think I could complete my book in five or six days, if I had nothing else to do; but I have seldom one hour free from interruption. Letters come that must be answered—visitants that must be received—business that must be attended to. I have a good many sheep and lambs to look after — sick and afflicted souls dear to the Lord; and therefore whatever stands still — these must not be neglected. Among these various avocations, night comes before I am ready for noon, and the week closes when, according to the state of my business, it should not be more than Tuesday! Oh precious irrecoverable time! Oh that I had more wisdom in redeeming and improving you! Pray for me, that the Lord may teach me to serve him better.

Mrs. Newton has been one week confined to her chamber through illness — but is pretty well again. We abound in mercies and causes for gratitude; but what a shame and pity to make such poor returns to the Author of them! I long to come to Newport to see you — but I believe I must wait for that pleasure until the days are a little longer. In the meantime you will be as welcome to us here, if you will trot over — as a new guinea to a miser's pocket.

I am very affectionately yours,

John Newton

January 27, 1778

Naughty Sir,

To keep me at home four afternoons upon the tip-toe of expectation — and not come near me at last. If you cannot send me a certificate, signed by the doctor and church-warden, specifying that you were too ill to travel, I have reason to be angry with you! But to show my forgiving spirit, if you will come over on Monday To dinner, I will give you something to eat, and your certificate of pardon.

I am to preach (if I can) three times on Fast-day — but have at present fixed only upon one text, which, for a certain reason, I shall not mention to you at present. I send you, however, according to order, a text and a plan which I found among my old papers. I preached it about sixteen years ago to a congregation of about twelve, in my own house, sometime before I was brought into the public ministry. I have not time to read it over; but if it may put any hints in your way, it is at your service. I cannot send you my present thoughts upon another text, for a plain reason, namely, that I am not able yet to think for myself; and I must receive — before I can communicate. It would be mocking you to offer you drink — out of an empty vessel.

Since I have begun to write, I have thought perhaps one of my texts will be either Psalm 97:1, or Psalm 19:1. The whole system of my politics is summed up in that one sentence, "The Lord reigns!" I wish you would send me, by the bearer, some hints towards a sermon on it. It would be a good text if I knew how to manage it.

The times look awfully dark indeed; and as the clouds grow thicker, the stupidity of the nation seems proportionally to increase. If the Lord had not a remnant here, I would have very formidable apprehensions. But he loves his children; some are sighing and mourning before him, and I am sure he hears their sighs, and sees their tears. I trust there is mercy in store for us at the bottom; but I expect a shaking time before things get into a right channel, before we are humbled, and are taught to give him the glory.

The state of the nation, the state of the churches — both are deplorable. Those who should be praying — are disputing and fighting among themselves! Alas! how many professors are more concerned for the mistakes of government, or of the Americans, than for their own sins! When will these things end?

Love me, and pray for me, and come to see me — for I cannot come to you. With my love and Mrs. Newton's to you and Mrs. Bull,

I remain, your obliged friend,

John Newton Olney, 24 Feb., 1778.

Dear Sir,

I am so monstrous busy, I have hardly time to tell you how sorry I am for my disappointment, and your illness, which was the cause of it. Indeed, I am as sorry for both, as a Calvinist ought to be. It was the time you and I appointed for meeting; had it been the Lord's time — nothing could have prevented you. I wish he may give you permission to come next Monday, or any day after tomorrow which you please, only send word. What do you think of it? I have a double motive for wishing to see you now, because, besides having your company, it would be a proof that you were better.

Last Sunday afternoon we had a great personage with us at church. I endeavored to persuade all the congregation to kiss Him. But though I talked a whole hour about it, few would comply. Alas! it was because they did not know him; and though I told them who he was, they would not believe me.

Dear Sir,

When I found the morning coaches came in without you, I was not much disappointed. I know how difficult it is to get away from Northampton if you are seen in the street after breakfast. The horseleech has three daughters, saying, Give, give! The cry there is, Preach, preach. When you have told them all, you must tell them more, or tell it them over again. Whoever will find tongue — they will engage to find ears. Yet I do not blame this importunity. I wish you were teased more with it in your own town; for though undoubtedly there are too many both at Northampton and here whose religion lies too much in hearing — yet, in many, it proceeds from a love to the truth, and to the ministers who dispense it. And I generally observe that those who are not willing to hear a stranger (if his character is known) are indifferent enough about hearing their own minister.

I beg you to pray for me. I am a poor creature, full of needs. I seem to need the wisdom of Solomon, the meekness of Moses, and the zeal of Paul — to enable me to make full proof of my ministry. But, alas! you may guess the rest.

Send me "The Way to Christ"! I am willing to be a debtor to the wise and unwise, to doctors and shoe-makers, if I can get a hint, or a Nota Bene from anyone, without respect to parties.

When a house is on fire, Churchmen and Dissenters, Methodists, Papists, Moravians, and Mystics — are all welcome to bring water. At such times nobody asks, "Dear friend, what church do you worship at?" Or "What do you think of the five points?"

Love and thanks to Mrs. Bull, etc,

John Newton

28th April, 1778.

Dear friend,

My dear wife has been quite ill. Her head was ill when at your house — but she can carry it off pretty well, if not quite bad, for her spirits are naturally very good, which is a great mercy. Sickness is a bitter pill to the flesh — but good natural spirits sweeten the pill, if I may so say, and make it rather more palatable.

The Lord is good; he knows what we need, and when we need it; and then have it we must and shall — whether it be sweet, bitter, or sour, for he will withhold no good thing from those who fear and love him. He weighs the mountains in scales, and the hills in a balance; with equal accuracy he adjusts all that concerns us. Worms as we are, he is attentive to everything that relates to our peace and welfare, as though we, each of us singly, were the sole objects of his providential care. At the same time, he is providing for the lions and ravens, supporting all the ants and worms that creep upon the earth; at the same time he upholds and enlightens the inhabitants of the heavenly world. His eye and his heart are attentively fixed upon you and worthless me. Well may we say, "Who is a God like unto you!"

Affectionately yours,

John Newton Olney 1st July, 1778.

July 7, 1778

My dear friend,

I don't know that I have anything to say worth the postage, though perhaps, had I seen you before you set off, something might have occurred which will not be found in my letter. Yet I write a line, because you bid me, and are now in a far foreign country. You will find Mr. **** a man to your tooth—but he is in Mr. W****'s connection. So I remember Mr. Bede, after giving a high character of some contemporary, kicks his full pail of milk down, and reduces him almost to nothing, by adding in the close to this purpose; "But, unhappy man—he did not keep Easter our way!" I don't care a fig for all such religious connections! Therefore I venture to repeat it, that Mr. ****, though he often sees and hears Mr. W****, and I believe loves him well, is a good man—and you will see the invisible mark upon his forehead, if you examine him with your spiritual spectacles.

I do pity you in London! I see you melted with heat, stifled with smoke, stunned with noise! Ah! what a change from the brooks, and bushes, and birds, and green fields—to which you lately had access. Of old they used to retire into the deserts for contemplation and meditation. If I was to set myself a moderate penance—it might be to spend two weeks in London in the height of summer! But I forget myself. I hope the Lord is with you—and then all places are alike. He makes the dungeon and the stocks comfortable, Acts 26. Yes, even a fiery furnace, and a lion's den! A child of God in London—seems to be in all these trying situations—but Jesus can preserve His own people. I honor the grace of God in those few (comparatively few, I fear,) who preserve their garments undefiled in that Sardis! The air is filled with infection; and it is by God's special power and miraculous preservation, that they enjoy spiritual health—when so many sicken and fall around them on the right hand and on the left. May the Lord preserve you from the various epidemic soul diseases which abound where you are—and may He be your comfort and defense from day to day.

Last week we had a lion in town. I went to see him. He was wonderfully tame; as friendly with his keeper, as docile and obedient as a pet dog. Yet the man told me he had his surly fits, when they dared not touch him. No looking-glass could express my face more justly—than this lion did my heart. I could trace every feature—as wild and fierce by nature; yes, much more so—but grace has in some measure tamed me. I know and love my Keeper, and sometimes watch his looks that I may learn his will. But, oh! I have my surly fits too! Seasons when I relapse into the savage again, as though I had forgotten all.

July 13, 1778

My dear friend,

As we are so soon to meet, as I have nothing very important to communicate, and many things occur which might demand my time; I have no other plea to offer, either to you or myself, for writing again—but because I love you.

I pity the minister with whom you talked this morning. But we must take men and things as we find them—and when we fall in company with those from whom we can get little other good, it is likely we shall at least find occasion for the exercise of patience and charity towards them, and of thankfulness to him who has made us to differ. And these are good things, though perhaps the occasion may not be pleasant. Indeed, a Christian, if in a right spirit, is always in his Lord's school, and may either learn a new lesson, or how to practice an old one—by everything he sees or hears, provided he does not willfully tread upon forbidden ground. If he were constrained to spend a day with the poor creatures in Newgate prison, though he could not talk with them of what God has done for his soul, he might be more sensible of God's mercy, by the contrast he would observe around him. He might rejoice for himself—and mourn over them—and thus perhaps get as much benefit as from the best sermon he ever heard!

It is necessary, all things taken together, to have interaction more or less, with narrow-minded people. If they are, notwithstanding their prejudices, civil to us—they have a right to some civility from us. We may love them, though we cannot admire them; and pick something good from them, notwithstanding we see so much to blame. It is perhaps the highest triumph we can obtain over bigotry—when we are able to bear with bigots themselves. For they are a set of troublesome folks, whom Mr. Self is often very forward to exclude from the comprehensive love and tenderness which he professes to exercise towards those who differ from him.

I am glad your present home (a believer should be always at home) is pleasant; the rooms large and airy; your host and hostess kind and spiritual; and, upon the whole, all things as well as you could expect to find them, considering where you are. I do not wish you to live there, for my own sake as well as yours—but if the Lord should so appoint it—I believe he can make you easy there, and enable me to make a tolerable shift without you. Yet I certainly shall miss you; for I have no person in this neighborhood with whom my heart so thoroughly unites in spiritual things, though there are many whom I love.

Conversation with most Christians is something like going to court; where, except you are dressed exactly according to a prescribed standard, you will either not be admitted, or must expect to be gaudily stared at. But you and I can meet and converse without pretense, without fear of offending, or being accounted offenders, for a word out of place, and not exactly in the right mode.

I think my sentiments and experience are as orthodox and Calvinistic as need be; and yet I am a sort of speckled bird among my Calvinist brethren. I am a mighty good Churchman—but pass among them as a secret Dissenter. On the other hand, the Dissenters (many of them I mean) think me defective, either in understanding or in conscience, for staying where in the church. Well! there is a middle party, called Methodists—but neither do my dimensions exactly fit with them. I am somehow disqualified for claiming a full brotherhood with any party. But there are a few among all parties who bear with me and love me—and with this I must be content at present. But so far as they love the Lord Jesus, I desire, and by his grace I determine (with or without their permission) to love them all. Church denomination walls, though stronger than the walls of Babylon, must come down in the general ruin, when the earth and all its works shall be burnt up, if no sooner!

My dear friend,

I thought that it pleased your very heart to see so much simplicity and spirituality in a lady of fortune. It is not wealth — but the love of it, and the pride of it, which are hurtful to professors. I know several people of distinction, who are as eminent for humility and devotedness to God — as for their rank in life. And, through mercy, I have no intimacy with any in a line of life above me, but what I think are such. It is the triumph of grace — to make the rich humble, and the poor thankful.

Oh, the gospel is an admirable expedient, a cure-all, equally suited to every condition of life, a universal cordial, a sovereign antidote! Those who truly receive it, are qualified to live in every situation to which the Lord in his providence appoints them. Though the air is infected, and thousands fall around them — they shall flourish, for the grace of their Lord is always sufficient for them, and the truths upon which they feed keep them from being either elated by prosperity, or depressed unduly by trials. Everywhere, and in all things, they are instructed. They hear the voice of their Beloved, are guided by his eye, animated by his example, and cheered by his presence!

I love you a little better than I did, because you know and love Dr. Conyers. I am not fond of making comparisons between ministers, and yet am almost constrained to set him at the head, as the first of "the first three" of our line. But I should not do so, upon the account of his gifts as a minister, if I did not know he is little in his own eyes. I estimate a minister's character from combining what he is in the pulpit — with what he is when out of it; and they stand highest upon my scale, whose conduct is most expressive of the doctrines they preach.

If we cannot attain to "the first three," or to be ranked among "the thirty," still it is a mercy to be on the Lord's side, and to be honored with an employment in his family, though in a lower place, so we may but be enabled to say, "I do a little for him, and to feed a few of the weakest and poorest of his children, for his sake."

Especially ought I to think so, who was before a blasphemer and a reviler! That I, who once deliberately renounced him, despised his blood, and crucified him afresh, that I should be redeemed and saved from the wilds of Africa, and put in trust with the blessed gospel — this was mercy indeed. I am ready to say —

"The first archangel never saw

So much of grace before."

And yet I am not duly affected with it. Oh stupid, cold creature, to be no more humbled, no more thankful!

I am sincerely yours,

John Newton Olney, 18th July, 1778.

July, 1778

My dear friend,

I was glad to hear that you were again within a few miles of me; and I praise the Lord, who led you out and brought you home in safety, and preserved all in peace while you were abroad, so that you found nothing very painful to embitter your return. Many go abroad in health—but return no more. The affectionate wife, the prattling children, listen for the well-known sound of papa's foot at the door—but they listen in vain! A fall or a fever has intercepted him, and he is gone—far, far away. Some leave all well when they go from home—but how changed, how trying, the scene when they come back! In their absence, the Lord has taken away the desire of their eyes with a stroke! Or perhaps ruffians have plundered and murdered their family in the dead of the night—or a fire has devoured their habitation!

Ah! how large and various is the list of evils and calamities with which sin has filled the world! You and I have escape them. We stand, though in a field of battle, where thousands fall around us—only because the Lord is pleased to keep us. May He have the praise—and may we only live to love and serve him.

My wife has been very ill, and my heart often much pained while you have been absent. But the Lord has removed his hand—she is much better, and I hope she will be seen in his house tomorrow. I have few trials in my own person—but when the Lord afflicts her, I feel it. It is a mercy that he has made us one—but it exposes us to many a pain, which we might have missed if we cared but little for each other. Alas! there is usually an ounce of the golden calf, of idolatry and dependence, in all the warm regard we bear to creatures! For this reason, our sharpest trials usually spring from our most valued comforts.

I cannot come to you; therefore you must come hither speedily. Be sure to bring Mr. B**** with you. I shall be very glad to see him, and I long to thank him for binding my book. It looks well on the outside, and I hope to find it sound and savory. I love the author, and that is a step towards liking the book. For where we love—we are generally tender, and favorably take everything by the best handle, and are vastly full of candor. But if we are prejudiced against the author, the poor book is half condemned before we open it. It had need be written well; for it will be read with a suspicious eye, as if we wished to find treason in every page.

I am glad I profited you by calling myself a speckled bird. I can tell you, such a bird in this day, that wears the full color of no sect or party, is a rare breed; if not quite so scarce as the phoenix—yet to be met with but here and there. It is impossible I should be all of one color, when I have been a debtor to all sorts; and, like the jay in the fable, have been indebted to most of the birds in the air for a feather or two. Church and Dissenter, Methodist and Moravian, may all perceive something in my coat taken from them. None of them are angry with me for borrowing from them—but then, why could I not be content with their color, without going among other flocks and coveys, to make myself such a motley figure? Let them be angry; if I have culled the best feathers from all, then surely I am finer than any!

I am sincerely yours,

John Newton

Dear Mr. Bull,

When you are with the King, and are getting good for yourself, speak a word for me and mine. I have reason to think you see him oftener, and have nearer access to him than myself. Indeed, I am unworthy to look at him, or to speak to him at all — much more that he should speak tenderly to me; yet I am not wholly without his notice: he supplies all my needs, and I live under his protection. My enemies see his Royal arms over my door, and dare not enter. Were I detached from him for a moment, in that moment they would make an end of me.

I am, as I ought to be, your affectionate and obliged,

John Newton

My birthday, 4th August, 1778.

August, 1778

Dear friend,

If the Lord affords health; if the weather be tolerable; if no unforeseen change takes place; if no company comes in upon me tonight, (which sometimes unexpectedly happens,) with these provisos, Mr. S **** and I have engaged to travel to **** on next Monday, and hope to be with you by or before eleven o'clock!

In such a precarious world, it is needful to form our plans at two days' distance, with precaution and exceptions, James 4:13. However, if it be the Lord's will to bring us together, and if the purposed interview is for his glory and our good, then I am sure nothing shall prevent it. And who in his right wits would wish either to visit or be visited upon any other terms? O! if we could but be pleased with his will, we might be pleased from morning to night, and every day in the year.

Pray for a blessing upon our coming together. It would be a pity to walk ten miles to pick straws, or to come with our empty vessels upon our heads, saying, "We have found no water!"

My dear friend,

I was unwilling not to leave a line to tell you that we sympathize with you and Mrs. Bull in your severe trial. (The death of an infant.) But, at the same time, I rejoice exceedingly in the Lord's goodness, enabling you to be resigned and satisfied with his will, despite all the feelings and pinchings of flesh and blood. Had the child lived, the warmest desires of a parent's heart for him could only have been, that he might at last have arrived to that rest and happiness, to which the Lord has now brought him by a shorter cut. Saving thereby him from many troubles, and you from some occasional heartaches, which must otherwise have been experienced. If you can now believe and say, "He does all things well" — with what transport would you say it, if the whole plan of his wisdom and love was unfolded to your view? He will condescend to unfold it to you hereafter, and it will fill you with admiration. Your tender plant is now housed, out of the reach of storms. It is an affliction, to be cordially rejoiced in, when the Lord, who cares for us, intimates his will by the event.

What a blessing to be a Christian — to have a hiding place and a resting place always at hand! To be assured that all things work for our good, and that our compassionate Shepherd has his eye always upon us, to support and to relieve us. The flesh will feel the sharp affliction — but faith and prayer will lighten the burden, and heal the wound. Daily your sense of the Lord's goodness will increase, and the sense of pain will abate, so that you will have less sorrow, and more joy, from day to day.

The Lord favored us with a tolerable day yesterday, and I hope he was in the midst of us — yet, upon the whole, we have but slack times. Oh for a revival, a day of Pentecost, a visible accomplishment of that gracious promise, Ezekiel 34:6! I trust my soul desires it; but, alas! my desires are faint and cold. My subjects yesterday were, forenoon, Psalm 142:1,2; afternoon, 1 Corinthians 10:12, a watch word. In the evening, a hymn about the sheep and the Shepherd, how he dwells among them, and they lie around in safety at his feet. They are surrounded by wolves, visible and invisible — these growl and thirst for blood; but the Shepherd's eye controls them. He stands and feeds his sheep in the midst of their enemies, who grudge and snarl — but cannot prevail against the sheep, helpless as they are, because the Lord is their Shepherd.

Pray for your poor friend and brother,

John Newton

Olney, 7th Sept., 1778, Monday.

October 27, 1778

My dear friend,

I have been witness to a great and important revolution this morning, which took place while the greatest part of the world was asleep. Like many state-revolutions, its first beginnings were almost indiscernible—but the progress, though gradual, was steady—and the event decisive. A while ago darkness reigned. Had a man from space then dropped, for the first time, into our world—he might have thought himself banished into a hopeless dungeon. How could he expect light to rise out of such a dark state? And when he saw the first glimmering of dawn in the east, how could he promise himself that it was the forerunner of such a glorious sun as has since arisen! With what wonder would such a new-comer observe the bounds of his view enlarging, and the distinctness of objects increasing from one minute to another; and how well content would he be to part with the twinkling of the stars, when he had the broad day all around him in exchange! I cannot say this revolution is extraordinary, because it happens every morning—but surely it is astonishing, or rather it would be so—if man was not astonishingly stupid!

We were once such strangers! Darkness, gross darkness, covered us. How confined were our views! And even the things which were within our reach—we could not distinguish. Little did we then think what a glorious day we were appointed to see; what an unbounded prospect would before long open before us! We knew not that there was a Sun of Righteousness, and that he would dawn, and rise, and shine upon our hearts. And as the idea of what we see now—was then hidden from us, so at present we are almost equally at a loss how to form any conception of the stronger light and brighter prospects which we wait and hope for. Comparatively we are still in the dark—at the most, we have but a dim twilight, and see nothing clearly—but it is the dawn of immortality, and a sure presage and earnest of glory.

Thus, at times, it seems a darkness that may be felt broods over your natural spirits—but when the day-star rises upon your heart, you see and rejoice in his light. You have days as well as nights; and after a few more vicissitudes, you will take your flight to the regions of everlasting light, where your sun will go down no more. Happy you, and happy I—if I shall meet you there, as I trust I shall. How shall we love, and sing, and wonder, and praise the Savior's name!

Last Sunday a young man died here of extreme old age, at twenty-five. He labored hard to ruin a good constitution, and unhappily succeeded—yet amused himself with the hopes of recovery almost to the last. We have a sad multitude of such poor creatures in this place, who labor to stifle each other's convictions, and to ruin themselves and associates, soul and body!

How industriously is Satan served! I was formerly one of his most active under-tempters! Not content with running down the broad way which leads to destruction by myself—I was indefatigable in enticing others! And, had my influence been equal to my wishes—I would have carried the whole human race to hell with me! And doubtless some have perished, to whose destruction I was greatly instrumental, by tempting them to sin, and by poisoning and hardening them with principles of infidelity. And yet I was spared! When I think of the most with whom I spent my ungodly days of ignorance, I am ready to say, "I alone have escaped alive!"

Surely I have not half the activity and zeal in the service of Him who snatched me as a brand out of the burning—as I had in the service of His enemy! Then the whole stream of my endeavors and affections went one way; now my best desires are continually crossed, counteracted, and spoiled, by the sin which dwells in me! Then the tide of a corrupt nature bore me along; now I have to strive and swim against it.

The Lord has cut me short of opportunities, and placed me where I could do but little mischief—but had my abilities and opportunities been equal to my heart desires—I would have been a monster of profaneness and profligacy! A common drunkard or profligate is a petty sinner—compared to what I once was. I had unabated ambition, and wanted to rank in wickedness among the foremost of the human race! "O to grace how great a debtor—daily I'm constrained to be!" "By the grace of God—I am what I am!" 1 Corinthians 15:10

But I have rambled. I meant to tell you, that on Sunday afternoon I preached from "Why will you die?" Ezekiel 33:10-11. I endeavored to show poor sinners, that if they died—it was because they would; and if they would—they must. I was much affected for a time. I could hardly speak for weeping, and some wept with me. From some, alas! I can no more draw a tear or a serious thought, than from a millstone!

November 27, 1778

My dear friend,

You are a better expositor of Scripture than of my speeches—if you really inferred from my last that I think you shall die soon. I cannot say positively you will not die soon, because life at all times is uncertain. However, according to the doctrine of probabilities, I think, and always thought, you bid fair enough to outlive me. The gloomy tinge of your weak spirits—led you to consider yourself much worse in point of health than you appear to me to be.

In the other point I dare be more positive, that, die when you will—you will die in the Lord. Of this I have not the least doubt; and I believe you doubt of it less, if possible, than I, except in those darker moments when the evil humor prevails.

I heartily sympathize with you in your illnesses—but I see you are in safe hands! The Lord loves you—and He will take care of you. He who raises the dead—can revive your spirits when you are cast down. He who sets bounds to the sea, and says "Hitherto shall you come, and no further," can limit and moderate those illnesses which sometimes distresses you. He knows why He permits you to be thus exercised. I cannot assign the reasons—but I am sure they are worthy of His wisdom and love, and that you will hereafter see and say, "He has done all things well!"

I do not like to puzzle myself with second causes, while the first cause is at hand, which sufficiently accounts for every phenomenon in a believer's experience. Your constitution, your situation, your temper, your distemper, all that is either comfortable or painful in your lot—is of his appointment! The hairs of your head are all numbered. The same power which produced the planet Jupiter—is necessary to the production of a single hair! Nor can one your hairs fall to the ground without His notice—any more than the stars can fall from their orbits! In providence, no less than in creation—He is the absolute Sovereign and Ruler.

Therefore fear not—only believe. Our sea may sometimes be stormy—but we have an infallible Pilot, and shall infallibly gain our port!

My dear friend,

I have heard of Mr. Palmer's dismissal from this state of sin and pain. Though old people must die, the stroke will be felt by near friends whenever it comes. But the loss of those who die in the Lord should not be long or deeply mourned. They are gone a little before us — and we hope to meet them soon again, and upon far better terms, when there will be no abatement of joy, and when joy shall have no end. I hope Jesus, the everlasting Father, who never dies, will comfort and bless his wife under all changes and events.

I hope your weak spirits, strengthened by the great and good Spirit of the Lord, have happily surmounted what you have lately had to go through, and that you rejoice to think that in less than a hundred years your turn will come to go and see your Beloved, and that in the mean time you will preach, and act, and speak for him as much as possible. When will you come and tell me something about him? Let me expect you on Friday, or any day but Wednesday, because I shall then be at Weston. My dear wife is tolerably well at present — but sometimes complaining a little; I should say, ailing; for I hope she is sensible she has no reason to complain. I write in great haste. Adieu; may the Lord bless you.

I am yours entirely,

John Newton

October, 1778

My dear friend,

Your letters are always welcome; the last doubly so, for being unexpected. If you never heard before, of a letter of yours being useful, I will tell you for once, that I get some pleasure and instruction whenever you write to me. And I see not but your call to letter-writing is as clear as mine, at least when you are able to put pen to paper.

I must say something to your queries about 2 Samuel 14. I do not approve of the scholastic distinctions about inspiration, which seem to have a tendency to explain away the authority and certainty of at least one half of the Bible. Though the penmen of Scripture were ever so well informed of some facts, they would, as you observe, need express, full, and infallible inspiration, to teach them which things the Lord would have selected and recorded for the use of the church, among many others which to themselves might appear equally important.

However, with respect to historical passages, I dare not pronounce positively that any of them are, even in the literal sense, unworthy of the wisdom of the Holy Spirit, and the dignity of inspiration, Some, yes, many of them, have often appeared trivial to me—but I check the thought, and charge it to my own ignorance and temerity. It must have some importance, because I read it in God's book. On the other hand, though I will not deny that they may all have a spiritual and mystical sense, (for I am no more qualified to judge of the deep things of the Spirit, than to tell you what is passing this morning at the bottom of the sea,) yet if, with my present quota of light, I would undertake to expound many passages in a mystical sense—I fear such a judge as you would think my interpretations fanciful and not well supported. I suppose I would have thought the Bible complete, though it had not informed me of the death of Rebekah's nurse, or where she was buried. But some tell me that Deborah is the law, and that by the oak I am to understand the cross of Christ—and I remember to have heard of a preacher who discovered a type of Christ crucified in Absalom hanging by the hair on another oak. I am quite a mole when compared with these eagle-eyed divines; and must often content myself with plodding upon the lower ground of accommodation and allusion; except when the New-Testament writers assure me what the mind of the Holy Spirit was, I can find the Gospel with more confidence in the history of Sarah and Hagar, than in that of Leah and Rachel; though, without Paul's help, I should have considered them both as family squabbles, recorded chiefly to illustrate the general truth—that vanity and vexation of spirit are incident to the best men, in the most favored situations.

And I think there is no part of Old Testament history from which I could not (the Lord helping me) draw observations, that might be suitable to the pulpit, and profitable to his people. But then, with the Bible in my hands, I go upon sure grounds. I am certain of the facts I speak from, that they really did happen. I may likewise depend upon the springs and motives of actions, and not amuse myself and my hearers with speeches which were never spoken, and motives which were never thought of, until the historian rummaged his pericranium for something to embellish his work. I doubt not, but were you to consider Joab's courtly conduct only in a literal sense, how it tallied with David's desire, and how gravely and graciously he granted himself a favor, while he professed to oblige Joab; I say in this view, you would be able to illustrate many important scriptural doctrines, and to show that the passage is important to those who are engaged in studying the anatomy of the human heart.

I have said enough or too much. I could, after all, preach very willingly upon God's devising means to bring his banished home again, and take occasion to lisp my poor views of that mysterious and adorable contrivance, without taking upon me to say that either Joab or the woman of Tekoa thought of the gospel when they cooked up that affair between them, or that even it was the express design of the Holy Spirit, in the place. These points are always true, and always to be remembered, asserted, and repeated:

1st. That man, by the entrance of sin, is a banished creature, driven far away from God, from righteousness, from happiness.

2nd. That he must have remained in this state of banishment forever, if God had not devised to bring him home again.

3rd. That these means are worthy the Divine contriver, full of glory, holiness, wisdom, and efficacy.

4th. Man, who was far off, is by faith actually restored and brought near by Jesus Christ.

Had it not been for Joab's courtly conduct, we would not have been favored with this expression, so apt and suitable for the basis of a gospel sermon; nor could I have been gratified with your thoughts upon the subject, or have had the pleasure of presenting you with mine.

I am sorry for your bodily complaints — but hope I may ascribe a part of them to low spirits; I am therefore unwilling to think you so bad as you think yourself. We are pretty well. Love to Mrs. Bull.

Believe me most sincerely yours,

John Newton

Dear Sir,

I shall expect you with earnestness on Tuesday, and I hope the weather, and especially illness, will not prevent you; and I beg you not to listen too much to that lowness of spirits which would persuade you, I suppose, to confine yourself always at home; because I am satisfied, that when you can muster strength to withstand this depressing, discouraging solicitation, and force yourself to ride and chat with some friend, you take the best course for relief; and, among all the friends you may think of treating with your company on such occasions, be sure none will be more glad to receive you than your friend at the Olney Vicarage!

I think my feelings will warrant me to make that line my own. The Lord has been pleased to put some grains of sympathy into my constitution; and the difficult turns of life I have passed through, have not been unuseful to give me some apprehension what impression afflictions make upon other people. It is true, I have not been much exercised with nervous complaints myself — but my situation here has afforded me a sort of second-hand experience of this kind, for I have lived almost fourteen years among a people dear to my heart, many of whom, to their other various trials, have that of a delicate and agitated nervous texture superadded, (owing in great measure, I suppose, to their sedentary and confined occupations,) which has given much scope to my observation and compassion.

I understand something of your complaint, and know how to pity you; but, since you say all is well, and shall be well — since you are in the wise and merciful hands of One who prescribes for you with unerring wisdom, and has unspeakably more tenderness than can be found in all human hearts taken together — I shall sorrow for you as though I sorrowed not; and I hope you will do the same for yourself. He weighs all your painful dispensations with consummate accuracy, and you shall not have a single grain of trouble more, not for a single moment longer — than he will enable you to bear, and will sanctify to your good.

As to our death — let it suffice us that it is precious in his sight. The how, the when, the where — every circumstance, is already planned by infinite wisdom and love. Satan may suggest that the hour will be terrible; but Jesus promises to be with us to lead us through the dark valley; and when we come to the brink of the river, I trust we shall find the ark there before us, to keep the waters down.

I have been preaching from a text tonight which I recommend as a suitable cordial for you in your present situation, Isaiah 41:17, "When the poor and needy seek water," etc. May the Lord himself apply and fulfill it to your comfort. Meditate upon it until you come, and then tell me more of it than I have been able to speak about it, which you may easily do, for I have only skimmed upon the surface and edge — of what has neither bottom nor bound.

I am running on as if you were on the other side of the Atlantic, or as though I had given up the hope of seeing you so soon as Tuesday. Come, if possible. I will endeavor to be alone, and will no more blab my expectation of your company, than I would if I had found a pot of honey, and was afraid of my neighbors breaking in upon me for a share.

Mrs. Newton joins in love, and will be glad to receive you, and will excuse you if you should feel but poorly. Our respects to Mrs. Bull. The rest when we meet. May the Lord come with you, then it will be a good visit.

I am affectionately and sincerely your friend, brother, and servant,

John Newton

Olney, 18 Dec, 1778, nine in the evening.

My dear friend,

You say you hate controversy — so do I; and therefore I beg nothing that passes between you and I, in our friendly researches after truth, may be included under so frightful a name. You and I may propose, debate, and sometimes differ — but I think it unlikely that we should ever dispute.

I am glad your fever is gone. I hope that all dark, unpleasant thoughts will vanish like mists before the midsummer sun, and that you will have a cheerful Christmas, a comfortable close of the old year, and a happy entrance upon the new.

I have not yet time to think of Christmas texts for this year — but I send you two old ones, if you can pick a hint or two it is well — and I and my hints will be honored.

My dear wife was very ill, indeed, last Wednesday night. After suffering about eight hours, the Lord relieved her. It seemed to me as if it might have been fatal in a few more hours. What a mercy to have an infallible Physician always within call, always in the house! Oh! what a precious present help in trouble! Help us to praise him. She is tolerable — but has not yet recovered the shock. She thanks you and Mrs. Bull for your love and returns it.

Adieu, in great haste — but always your most affectionate,

John Newton

Dear Sir,

Thank you for the savory dish which you sent me in your last post, I hashed it up my own way, and set it before my people on Christmas morning, and hope some of them fed heartily upon it. In the evening I preached from John 10:10.

What have you for New Year's day? I am not yet provided for the old folks in the forenoon. To the youth in the evening I think to preach from Jeremiah 3:19. Chiefly to resolve the difficulty which occurs among the children, considering them

1. as guilty

2. as obstinate.

Sovereign grace alone could surmount these difficulties. Grace has provided a Savior to take away the guilt, and the agency of the Holy Spirit to overcome the obstinacy, to give ground, liberty, and power to call God, Father: then all is easy. This is the principal thought I have in view. Pray for me, that I may open my mouth to speak boldly, plainly, affectionately, and successfully. We are tolerably well.

We wish you, and Mrs. Bull, a comfortable close of this year, and a happy entrance upon the next. And so with our joint love we bid you hearty farewell.

Yours in the best bonds,

John Newton

29th Dec.

My dear Mr. Bull,

My dear wife is ill again, a most violent pain in her head has lasted about thirty hours and, still continues. Pray for her; I wish you not to expect me either Tuesday or Wednesday. Mr. Scott and his wife are both very ill of a putrid fever. He caught it by attendance on the sick poor. A noble wound! Shall soldiers risk their lives, and stand as a mark for great guns, for sixpence a day, or for worldly honor? and is it not worth venturing something in imitation of Him who went about doing good, and when the good we aim at is for his sake? However, by his illness, and while it remains, I shall be confined at home that I may be within his call.

Love to Mrs. Bull. I am in great haste, and with great sincerity,

Your affectionate

John Newton

February 23, 1779

My dear friend,

On Saturday I heard you had been ill. Had the news reached me sooner, I would have sent you a letter sooner. I hope you will be able to inform me that you are now better, and that the Lord continues to do you good by every dispensation he allots you. Healing and wounding are equally from His hand—and are equally tokens of His love and care over us! "The Lord gives—andthe Lord takes away. Praise the name of the Lord!" Job 1:21.

I have but little affliction in my own person—but I have been oftened chastened of late by proxy. The Lord, for his people's sake, is still pleased to give me health and strength for public service. But, when I need the rod — he lays it upon my dear wife! In this way I have felt much—without being disabled or laid aside. But he has heard prayer for her likewise, and for more than a two weeks—she has been comfortably well. I lay at least one half of her sickness to my own account. She suffers for me, and I through her. It is, indeed, touching me in a tender part. Perhaps if I could be more wise, watchful, and humble—it might contribute more to the re-establishment of her health, than all the medicine she takes!

The last of my sermons was a sort of historical discourse, from Deut. 32:15; in which, running over the leading national events from the time of Wycliffe, I endeavored to trace the steps and turns by which the Lord has made us a fat and thriving people; and in the event blessed us, beyond his favorite Jeshurun of old, with civil and religious liberty, peace, honor, and prosperity, and Gospel privileges. How fat we were when the war terminated in the year 1763, and how we have kicked and forsaken the Rock of our salvation of recent years! Then followed a sketch of our present state and spirit as a people, both in a religious and political view. I startled at the picture while I drew it, though it was a very inadequate representation. We seemed willing to afflict our souls for one day, Isaiah 58:5. But the next day things returned into their former channel. The sermon seemed presently forgotten, except by a few simple souls, who are despised and hated by the rest for their preciseness, because they think sin ought to be lamented every day in the year.

Who would envy Cassandra her gift of prophecy upon the terms she had it—that her declarations, however true, should meet with no belief or regard by here hearers? It is the lot of all Gospel ministers, with respect to the bulk of their hearers. But blessed be the grace which makes a few exceptions! Here and there, one will hear, believe, and be saved. Everyone of these converts is worth a world! Our success with a few—should console us for all our trials.

Come and see us as soon as you can, only not tomorrow, for I am then to go to T****. My Lord, the Great Shepherd, has one sheep there, related to the fold under my care. I can seldom see her, and she is very ill. I expect she will be soon removed to the pasture above. Give our love to your dear wife.

John Newton

August 19, 1779

My dear friend,

Among the rest of temporal mercies, I would be thankful for pen, ink, and paper, and the convenience of the postal system, by which means we can waft a thought to a friend when we cannot be with him. My will has been to see you—but you must accept the will for the deed. The Lord has not permitted me.

I have been troubled of late with the rheumatism in my left arm. Mine is a sinful, vile body, and it is a mercy that any part of it is free from pain. It is virtually the seat and subject of all diseases—but the Lord holds them, like wild beasts in a chain, under a strong restraint. Was that restraint taken off, they would rush upon their prey from every quarter, and seize upon every limb, member, joint, and nerve—at once. Yet, though I am a sinner, and though my whole body is so frail and exposed, I have enjoyed for a number of years, an almost perfect exemption both from pain and sickness. This is wonderful indeed, even in my own eyes.

But my soul is far from being in a healthy state. There I have labored, and still labor, under a complication of diseases; and—but for the care and skill of an infallible Physician, I must have died long ago. At this very moment my soul is feverish, dropsical, paralytic. I feel a loss of appetite, a disinclination both to food and to medicine—so that I am alive by miracle. yet I trust I shall not die—but live, and declare the works of the Lord. When I faint he revives me again. I am sure he is able, and I trust he has promised to heal me—but how inveterate must my disease be, that is not yet subdued, even under his management!

Well, my friend, there is a land where the inhabitants shall no more say, "I am sick." Then my eyes will not be dim, nor my ear heavy, nor my heart hard! One sight of Jesus as he is—will strike all sin forever dead!

Blessed be his name for this glorious hope! May it cheer us under all our present uneasy feelings, and reconcile us to every cross. The way must be right, however rough, that leads to such a glorious end!

O for more of His gracious influence, which in a moment can make my wilderness-soul rejoice and blossom like the rose! I want something which neither critics nor commentators can help me to. The Scripture itself, whether I read it in Hebrew, Greek, French, or English, is a sealed book in all languages, unless the Spirit of the Lord is present to expound and apply it to my heart! Pray for me. No prayer seems more suitable to me than that of the Psalmist. "Bring my soul out of prison, that I may praise your name."

John Newton

April 23, 1779

My dear friend,

May I not style myself a friend, when I remember you after the interval of several weeks since I saw you, and through a distance of sixty miles? But the truth is, you have been neither absent nor distant from my heart for even a day. Your idea has traveled with me; you are a kind of familiar, very often before the eye of my mind. This, I hope, may be admitted as a proof of friendship.

I know the Lord loves you, and you know it likewise. Every affliction affords you a fresh proof of it. How wise is his management in our trials! How wisely adjusted in season, weight, continuance, to answer his gracious purposes in sending them! How unspeakably better to be at his disposal—than at your own! So you say; so you think; so you find. You trust in him, and shall not be disappointed. Help me with your prayers, that I may trust him too, and be at length enabled to say without reserve, "What you will, when you will, how you will." I had rather speak these three sentences from my heart, in my mother-tongue, than be master of all the languages in Europe.

August 28, 1779

My dear friend,

I want to hear how you are. I hope your illness is not worse than when I saw you. I hope you are easier, and will soon find yourself able to move about again. I would be sorry, if, to the symptoms of the kidney stone, that you would have the gout in your right hand—for then you will not be able to write to me.

We go on much as usual; sometimes very poorly, sometimes a little better—the latter is the case today. My rheumatism continues—but it is very moderate and tolerable. The Lord deals gently with us, and gives us many proofs—that he does not afflict willingly.

The days speed away apace! Each one bears away its own burden with it—to return no more. Both pleasures and pains which are past—are gone forever. What is yet future will likewise be soon past. The final end will soon arrive! O to realize the thought, and to judge of things now in some measure suitable to the opinion we shall form of them, when we are about to leave them all! Many things which now either elate or depress us—will then appear to be trifles as light as air!

One thing is needful—to have our hearts united to the Lord in humble faith; to set him always before us; to rejoice in him as our Shepherd and our portion; to submit to all his appointments, not of necessity, because he is stronger than us—but with a cheerful acquiescence, because he is wise and good, and loves us better than we do ourselves; to feed upon his truth; to have our understandings, wills, affections, imaginations, memory—all filled and impressed with the great mysteries of redeeming love; to do all for him, to receive all from him, to find all in him. I have mentioned many things—but they are all comprised in one, a life of faith in the Son of God. We are empty vessels in ourselves—but we cannot remain empty. Except Jesus dwells in our hearts, and fills them with his power and presence, they will be filled with folly, vanity, and vexation.

My dear friend,

I have been at the great house.* I could have wished for a more favorable account of your illness — but you are in the Lord's hand — in the hand of Him who loves you better than I do — better than you can love yourself! He will therefore order all things concerning you, and give you strength according to your day. This great Physician can support and heal — when other physicians are found to be of no value.

I am waiting with suspense for a further account of the war-fleets. If the news proves unfavorable, it will come soon enough to us all. Now perhaps is the crisis, or perhaps before now the blow is struck. My soul, wait only upon God — he directs the storm, and he can hush it into a calm. He loves his people, and numbers the hairs of their head. Whatever may be his purpose towards the nation, he says to his own people — it shall be well with them.

Here I was interrupted by a visit from Mrs. Foster; she has just left us, and I am just going to the great house and therefore cannot fill up my paper as usual. I wish the bearer may bring me a better account of you. May the Lord fill you with his peace. We join in love to you and Mrs. Bull. I am constrained to subscribe myself in haste,

Affectionately yours,

John Newton

Olney, 7 Sept. 1779.

* What is called the great house, was an ancient mansion, then unoccupied, and now pulled down, in which Mr. Newton rented a room, where meetings were held for prayer, and exposition of the word of God. In this room Mr. Bull sometimes preached for Mr. Newton. I have by me a list of names, in the hand-writing of Mr. Newton, of these letters, of the people who engaged in prayer; and it is interesting to observe among them the frequent recurrence of the name of the poet William Cowper, from the year when he came to reside at Olney, to the year 1773, when a dark cloud came over his mind, and peculiar views of himself unhappily prevented him from entering a place of worship to the end of his days. So strictly conscientious was this interesting man, that I have frequently seen him sit down at table when others have risen to implore a blessing, and take his knife and fork in hand, to signify, I presume, that he had no "right to pray." "Prove to me" (he writes) "that I have a right to pray, and I will pray without ceasing, even in the belly of this hell, compared with which Jonah's was a palace, a temple of the living God." — Southey's "Cowper," vol. iv. p. 235.

My dear friend,

I wish you may be able to send us word by the bearer, that your illness is removed, or at least abated. If not, still I hope He favors you with soul peace and resignation to his will.

My race at the Olney church is nearly finished. I am about to form a connection for life with a church in Woolnoth, London. I hope you will not blame me; I think you would not if you knew all circumstances. However, my conscience, through mercy, is clear; and my path, in my own view, and in the judgment of several of my most spiritual friends, is plainly the path of duty. I hope and beg you will pray for me.

Indeed I am not elated at what the world calls preferment. London is the last situation I would have chosen for myself. The throng and hurry of the business world, and noise and party contentions of the religious world — are very disagreeable to me. I love woods and fields, and streams and trees; to hear the birds sing, the sheep bleat. I love retreat and rural life, such as I have been happy here for more than fifteen years. I thank the Lord for his goodness to me here. Here I have rejoiced to live; here I have often wished and prayed that I might die. I am sure no outward change can make me happier — but it does not befit a soldier, to choose his own post.

On Tuesday we purpose going to Northampton, and to return by Newport on Thursday, take a bit of dinner, and change a few expressions of love with you and Mrs. Bull, and home early in the afternoon, because I am to preach in the evening.

It is a weeping time with us at Olney — my people feel each one for themselves; but I must and do feel for them all. But I trust the Lord will provide them a pastor after his own heart.

Adieu. Pray for us. May the Lord bless you, both you, and your children.

I am most affectionately yours,

John Newton

Olney, 25 Sept. 1779.

My dear friend,

Do not say, do not think, that I have forgotten you. I have waited to tell you some news, until I can wait no longer. The Lord gave us a safe and comfortable journey, and my dear wife has been comfortably well since we came here. I delivered my presentation to the bishop's secretary on Friday last, and on Sunday I received notice that a caveat was lodged against my institution by some person or people who pretend to dispute Mr. Thornton's right of presenting. This counter-claim causes a delay or suspense — but, it is thought, will soon appear to be groundless.

However, through mercy, your poor friend feels himself very easy about the event. The affair is where I would have it — in the Lord's hand. If He fixes me here — I humbly hope and believe he will support me, and it shall be for good. If He appoints otherwise, I trust it will be no grief of heart to me to return to Olney, where I shall be within five miles of dear Mr. Bull. I am, however, glad I accepted the offer, whatever the outcome may be.

Noisy London, and its unsettled, hurrying kind of life — is not quite to my tooth! I believe if I settle in London, I shall entreat Him, in whose hands all my affairs, the greatest and the smallest, are, in his good providence — to prepare me a habitation somewhere about the outskirts of the town, where I may enjoy some measure of privacy, fresh air, and see the green fields and trees at no great distance from me. This will be the more feasible, as the parsonage house is occupied by the post office, which seems to furnish me with a fair excuse for not residing in the parish.

Though many things will occasionally force themselves upon my thoughts, I trust, in answer to your prayers for me, the Lord will help me to remember that one thing is needful — and, comparatively speaking, one only. It matters little whether I live and die in Olney or London — in the city or the suburbs — provided I am where He would have me be, favored with his light and grace and consolation — and qualified, by his holy anointing — to honor, love, and serve him, in whatever circumstances his wisdom may appoint.

Mr. Foster is now at Olney, and I have entered upon his services, which amount to eleven sermons in a two weeks. Upon my first coming there — I preached from 1 Thessalonians 5:25, "Brethren, pray for us;" when, after giving them some account of the difficulties and trials attending the ministerial office in general, I endeavored to engage the prayers of many in my behalf, with respect to the new prospect before me. Surely I shall need a singular communication of divine wisdom, zeal, meekness, and fortitude, in a London situation.

Brother, pray for me, and may the Lord enable you to pray in faith. My weaknesses are many. I am but a child to go in and out before a great people, and to stand in a conspicuous and important post. But the Lord is a good and all-sufficient Master, and I would wrong his goodness and faithfulness — were I to question his promise of strength according to my day. Should this relocation take place, I hope the outcome will show it is the Lord's doing. Had not the proposal come to me unexpected, unsolicited, I think I may honestly add, undesired — and so circumstanced, that neither my own judgment, nor the advice of some of my most spiritual friends would permit me to decline it, without a fear of opposing His will — I say, could I not view it in this light, I would be uneasy, and afraid of the experiment. But now I can trust that if God brings me hither — his presence will be with me. My poor mistaken people, by their hasty refusal of Mr. Scott, have given me a pain which I did not expect. But I cannot help it. May the Lord overrule it for good, and provide better pastor for them than they can expect.

While we can meet daily at a throne of grace, and exchange a letter when we please — let us not think ourselves far asunder. Your company has been pleasing and edifying to me, and I shall sensibly miss it. But our friendship will be inviolable. You have a near and warm place in my heart, and will retain it as long as life continues. I confidently expect the same on your part. I long to hear how you do — shall be thankful to know you are getting better, and especially to be told that all your painful dispensations are evidently sanctified, and that you have that peace which can exist and flourish in affliction. My dear wife joins in love to you and Mrs. Bull, and your two young plants. May the Lord make them plants of renown; may they increase in wisdom as in years, and grow up to his praise and your comfort.

Adieu. Send me a letter soon. And believe me to be most affectionately your faithful friend and brother,

John Newton

14th October, 1779.

October 26, 1779

(Mr. Newton refers to a severe trial through which Mr. Bull had passed three days before, in the sudden death of a dear child, five years old, after he had been bereaved of four other children, one only surviving.

The following is an extract from Mr. Bull's letter, dated Oct. 23, announcing this painful event:

Dear sir, pray for me. My bodily pain is great, the sorrow in my heart is real; but the love of the Lord is the same. Oh! how I rejoice in him this day, while I grieve in self. I seem to long to be where my dear Polly is; and, blessed be my God, I shall go there some day, perhaps soon. My dear lamb has revealed a peculiar sweetness of temper these three or four months, and a fondness for reading quite remarkable. For five or six weeks she had got up before me in the morning to read a Scripture chapter to me while I was dressing; and one day she cried very much because I got up before her. She gave me great delight by this practice, and it was her own. This is a pleasant tale to me, and you can excuse it. The lamb looks exceedingly beautiful now she is laid out; but, oh! my faith sees her spirit in the hands and heart of God my Savior, and that delights me. My dear wife is very poorly; and poor lonely Tommy is tolerable, and is kept for some future trial.

I wish that I may silently rejoice in my Savior for cutting off all sources of comfort, but himself. Indeed it does look as if he would have my whole heart, and would make everything else taste bitter that he may taste the sweeter. As lately as yesterday, my dear child read me Psalm 25 before I was up. Oh! how little did I think affliction and death were so near!)

My dear friend,

I feel for you a little in the same way as you feel for yourself. I bear a friendly sympathy in your late sharp and sudden trial. I mourn with that part of you which mourns—but at the same time I rejoice in the proof you have, and which you give, that the Lord is with you in truth. I rejoice on your account, to see you supported and comforted, and enabled to say, "He has done all things well!"

I rejoice on my own account. Such instances of his faithfulness and all-sufficiency are very encouraging. We must all expect times of trouble in our turns. We must all feel in our concernments, the vanity and uncertainty of creature comforts. What a mercy is it to know from our own past experience, and to have it confirmed to us by the experience of others—that the Lord is good, a stronghold in the day of trouble, and that he knows those who trust in him.

All creatures are like candles; they waste away—while they afford us a little light, and we see them extinguished in their sockets one after another. But the light of the sun makes amends for them all. The Lord is so rich that he easily can, so good that he certainly will—give his children more than he ever will take away! When his gracious voice reaches the heart, "It is I—do not be afraid! Be still—and know that I am God!" when he gives us an impression of his wisdom, power, love, and care—then the storm which attempts to rise in our natural passions is hushed into a calm; the flesh continues to feel—but the spirit is made willing, and something more than submission takes place—a sweet resignation and acquiescence, and even a joy that we have anything which we value, to surrender to his call.

Love and best wishes to you and Mrs. Bull from your most affectionate friend,

John Newton

My dear friend,

How are you? and what are you about? I am afraid that either your spirits are grown weak, or your memory fails you a little. Pluck up your courage; then remember how much you are beloved by a local sojourner, and send Dr. Ford a letter, or at least a note; if it be but three lines, he will gladly pay three-pence for them to the post-man.

The church in Woolnoth and I are not yet married. I told you somebody forbade the plans, and the prohibition is not yet taken off. Nothing has been done, or attempted to be, within these two days; but I believe we shall soon hasten into the midst of things. The Lord still enables me to abide by the surrender I made of the affair into his hands, and I wait the event with a tranquility almost approaching to indifference. However, in my private judgment, it appears much more probable that the bar will be removed, and the match take place, than the contrary. But until it is determined, I wish to consider it as an uncertainty.

To wed the church in Woolnoth — is in some respects pleasing; but then to be divorced from Olney — will be in many respects painful. Again, to leave Olney will free me from many known and sharply felt inconveniences; but then, to live in London may expose me to other trials, which though at present unknown, may be equally sharp to my feelings. What a comfort this, that when "I am in a strait between two, and what to choose I know not," the Lord will mercifully condescend to choose for me! What a comfort that when we are quite dead as to consequences — He has promised to see for us, with his infinite and unerring eye!

Tell Mrs. Bull we love you both, have felt for you both, and shall be glad to hear that you are both pretty well. The Lord loves you likewise — and therefore he afflicts you. He has given you grace — and therefore he appoints you trials, that the grace he has given may be preserved and manifested to his praise. He has made you a good soldier, and therefore he appoints you a post of honor. You are not merely to walk about in a soldier's coat, at a distance from the noise and danger of war, and to brandish your sword without any risk of meeting an enemy; but he sends you down to the field of battle. You feel as well as hear — that our profession is a warfare; and you feel as well as hear, likewise — that the Lord is with you, fights for you, and supports you with strength, and covers your head in the day of conflict.

Accept this love token, and pay me in kind. I have not time to enlarge. I wish you a good night and a good morrow. Tomorrow! It is the Lord's day. May we be in the Spirit. I think to be a hearer in the forenoon at the Brethren's Chapel — to hear Mr. Latrobe, if he preaches. In the afternoon (if I do not alter my mind), I shall say something myself about a treasure — and the earthen, worthless, brittle vessels the Lord is pleased to put it in, even into such a foul piece of clay as your very poor — but very affectionate friend,

John Newton

London, Nov. 20th, 1779.

My dear friend,

I must write a short letter today, for many of my friends will expect to hear the outcome of my long waiting in town. The Lord's hour came in due time, and yesterday the Bishop gave me the pastorate of St. Mary Woolnoth, and tomorrow I am to be inducted — that is, put into possession of the key and the bell-rope, and thereby installed in all the rights, uses, and profits of the employment. So the curate of Olney is now transplanted and placed in the number of the London rectors. How little did I think of this when I was living, or rather starving — when a slave in Africa!

"The sport of slaves,

Or, what's more wretched still, their pity."

But the Lord is Sovereign and Almighty. He chooses and does what is well-pleasing in his sight. Whom he will — he slays; whom he will — he keeps alive. What cause for praise, that it pleased him to extend his mercy to you and I.

Many wish me joy. You, I believe, will pray and wish for me — that I may have much grace, and be favored with wisdom, fidelity, zeal, and meekness suited to the demands of my new and important situation. Through mercy, I feel little in this new situation to elate me. I hope I see the Lord's hand and call in it, and so far it pleases me. My concern at leaving many whom I love dearly at Olney, and my solicitude about them — will in a good measure qualify things in the changes which otherwise are not disagreeable to flesh and blood. But I need not repeat this in a short letter, when I believe I have written to the same purpose already.

Thank you for your letter. Not having it with me, I cannot answer it particularly. In general I know you are afflicted — and comforted; sick — and well; sorrowful — yet always rejoicing. This checker-work will last while life lasts — but it will not last always. Deliverance is approaching, and in the meantime we know all things are dispensed to us by infinite wisdom — in number, weight, and measure — with a far greater accuracy than any doctor can adjust his medicines to the state and strength of his patients. My dear wife has a head-ache today — but I hope she will be better. When I tell her that I have joined her love with mine — to you and Mrs. Bull and Tommy, I am sure she will confirm it.

I hope to see Newport and Olney next week. I am in all places, and at all times, most affectionately yours,

John Newton

Dec. 1, 1779.

My dear friend,

Many an eager look I darted through my study-window this morning, in hopes of seeing you and your grey horse. I need not tell you I was sorry to miss my expected pleasure; but I was more sorry to learn the cause of your not coming, though I suspected it before I received your note. I long with a great longing to have you here — yet not so as to wish you should make the attempt at the price of pain and inconvenience to yourself. Supposing the Lord relieves you, and you are pretty well tomorrow, what do you think of coming — and returning when you have quite enough of us for one time? If I should be weary of you first, I will tell you so.

Until then I have two thoughts to comfort me:

1st, that we love each other;

2nd, that though we do we are not necessary to each other, your Lord and mine is equally near to us both; and a visit from him is sufficient to comfort either of us, though we were in the solitary situation of Robinson Crusoe.

Indeed, supposing you really have the stone, and that your pains are sharp and frequent, I would rather encourage you to submit to the operation, than dissuade you from it. But I understood that since you had changed your medicine, you were, in general, free from pain. I would hope that He whom you serve, would support you under the operation, and bring you safely through it. If you judge it expedient, therefore, come to London, and consult an able surgeon; but by no means commit yourself to a country practitioner.